Back in the days before I even knew what a piano quartet was, I would attend events at my school and bigger venues called “Battle of the Bands.” These were impromptu (sometimes rehearsed) sessions where the best bands around would get together, mix-‘n’-match their players, and generally revel in playing the music they loved. Some might find it blasphemous to equate a bunch of rock guys jamming with the concert presented on Sunday, January 22, in UNC’s Hill Hall, but that was one of the impressions I couldn’t help shake.

The concept of presenting recitals that are complete with respect to a composer’s output in a particular genre is nothing new. In the Triangle, we have been fortunate to hear some remarkable concerts along this line – the Ciompi Quartet playing all of Beethoven’s late string quartets over two evenings, the Borromeo Quartet’s marathon-like traversal of all six Bartók String Quartets, Fred Raimi and Jane Hawkins playing the complete works for cello and piano by Beethoven. However, I can’t recall having seen here – or even in listings elsewhere – a recital in which each work was played by a completely different set of musicians until this concert, when the three Piano Quartets of Brahms were given by three different groupings of artists. (Jonathan Bagg filled in for violist Dawn Hannay of the New York Philharmonic, so he was the only musician to play in two of the quartets.) This was not just a gimmicky stunt but an extremely rare opportunity to hear eleven of the finest musicians anywhere in one concert and to be able to contrast their different styles and approaches in similar music.

We live in an area that is remarkable for its musical camaraderie. It has become a common practice for one concert to include members of the music faculties of major universities in the area, principal players of the North Carolina Symphony, and talented freelancers. This concert was the epitome of that kind of partnership.

Brahms began work on all three of his piano quartets concurrently in the mid-1850s. He placed such importance on the first one, in g minor, Op. 25 (played last on this program) that he selected it for his debut as a pianist and composer in Vienna in 1862. The premiere of the second – in A major, Op. 26 – followed just two weeks later. These works are the essence of Brahms, showing mastery of large forms, contrapuntal virtuosity, rhythmic ambiguity, and lovely melding of piano and strings.

The first all-star team to take the stage was UNC faculty members Brent Wissick, cello, and Mayron Tsong, piano, Duke faculty member and Ciompi Quartet second violinist Hsaio-mei Ku, and Hugh Partridge, the Principal Violist of the NC Symphony, who also teaches at UNC. The A major Quartet is the only one of the three in a major key. Throughout much of the performance, I felt like I was listening to a piano trio because the viola’s lines were often inaudible. Part of this has to do with the unyielding tradition of having the violist’s instrument facing away from the audience – something which more aggressive players can overcome. I felt that, overall, there was some holding back in this performance – it could have been more emotionally revealing.

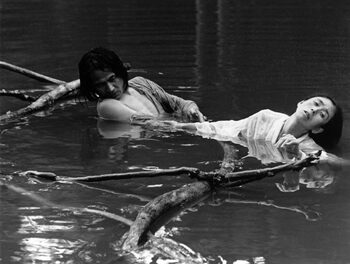

The second team played what is probably the most angst-ridden and wrenching of any work by Brahms – and that is saying a lot. Not completed until 1857, this was written at the transforming time in his life surrounding his love for Clara Schumann. The despair of this work is so great that Brahms himself suggested it be published with a picture of a man holding a pistol to his head. UNC violinist Richard Luby joined Duke faculty players Jane Hawkins, piano, Fred Raimi, cello, and Jonathan Bagg, viola. This is a group of musicians with many years of collaborations – quartets, piano trios, old friends, plus husband-wife…. These bonds were apparent as they plummeted to the depths of misery and back to the surface with such raw feeling that you could feel Brahms’ painful love. The Andante movement begins with one of those haunting, gorgeous cello lines like Brahms used in other slow movements – in his B major Piano Trio and in the Second Piano Concerto. Although I didn’t see any firearms put to any heads, this movement especially was played with depth, understanding, and technique that effectively portrayed the composer’s profound inner turmoil.

The first of the quartets was saved for last. Probably the best known of the three, the g minor quartet is an unforgettable powerhouse. Jonathan Bagg returned as violist and was joined by Ciompi Quartet-mate Eric Pritchard, violin, cellist Bonnie Thron, of the NCS, and UNC pianist Thomas Otten. Programming is an integral part of any concert, and selecting this quartet as the finale was an obvious choice. This was some of the finest chamber music playing I have ever heard, and the love and excitement beamed from the four players. Similar to the previous quartet as an extreme emotional roller coaster, this one ends with such electricity that you leave the concert crackling with energy. The final movement, labeled Rondo all Zingarese, is a gypsy-inspired bacchanal that reached speeds that had everyone’s heart rate climbing.

What an afternoon! From suicide warnings to an orgy of wild, earthy gypsy music, this was a concert to remember – an early inclusion to the best of 2006.