Racers, roadsters, racers-roadsters – 22 of them – have been given the space, attention, ballyhoo I would expect the North Carolina Museum of Art to lavish on a travelling show of 22 Rembrandts, Picassos, Matisses, though I might not see as many visitors as I saw last weekend wandering the galleries that harbored “Porsche by Design: Seducing Speed.”

Not that I would have it any other way: though some local critics have questioned the show’s aesthetic value, it places NCMA in a stream of major museums that have demanded that attention be paid to the design of objects other than painted canvas, carved marble, or etched paper.

Like a painted canvas, many of the autos on view are, in fact, hand-made, even numbered, each with its own history. Early on, we find the bright 1949 cream-colored “Type 356, Gmund Coupe,” the 17th in a run of about 50, their aluminum shells hand-hammered over a wooden armature. Its windswept design is the harbinger of decades of continuous aerodynamic modifications that grow more suave and alluring as we move about the rooms. But a Porsche sports car, of whatever vintage, is unmistakable, defined, according to Ken Gross, guest curator of the show, by “the arch of the roofline, the taut stance of the wheels, the car’s sense of purpose and motion.” They often have several incarnations, one for the highway, one for races.

Behind it all is the legendary Porsche family. In 1900 designer-engineer Ferdinand Porsche entered the industry in Austria, helping to create an electric racing car that outran gasoline-powered machines. Joining Daimler and Daimler-Benz, he oversaw an amazing run of racers through the twenties. Resettled in Germany, he developed a low sleek auto intended for a race from Berlin to Rome, one that never started because of Hitler’s war. Low, sleek, curvaceous, its hood and fenders sliding almost sexually against each other, a version of the car, “Porsche Type 64,” is domiciled at NCMA just outside the entry to the Porsche galleries. As in some other racers, its tiny cockpit is not made for comfort. (Tiny drivers?) During the war, the Porsche team also designed the Volkswagon at Hitler’s behest, though its immense popularity did not appear until well after the war when it could be mass-produced.

Turning from the small, neat “Type 356 Gmund Coupe,” its sisters and its cousins and its myriad offspring, to the autos designed exclusively as racers, we arrive at a very different machine: the thin, low-slung, “Type 804 F1.” Its huge wheels and long nose took it to first place in France’s Grand Prix and first and second place at Germany’s Solitude Grand Prix.

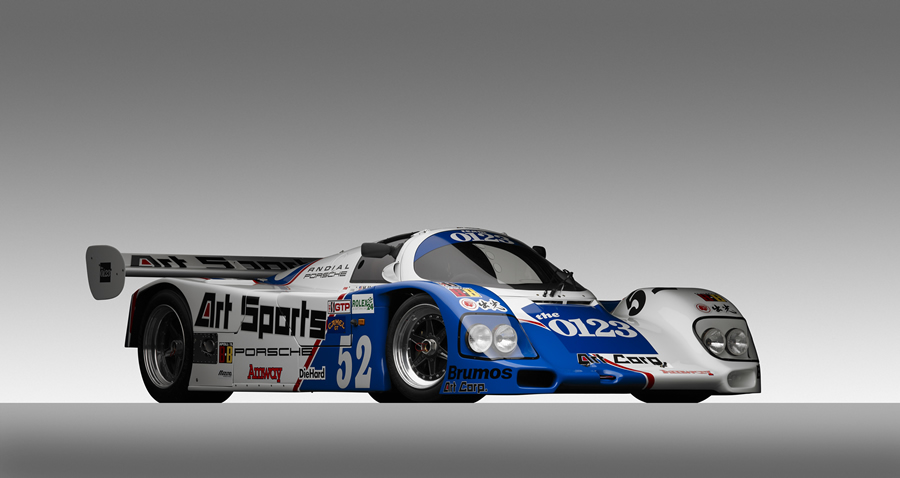

Other racers take any number of forms, most with a large “spoiler” at the rear. One of the most successful, winning ten world championships and 50 national championships was the 962 C (and its earlier version, the Porsche 956). As the catalogue notes, the design took downforce to a new level that greatly improved road holding. The example here, heavily painted in multi-colors and littered with ads, is lightened by an aluminum shell, its driver in a broad bubble between two broad fenders that rise toward the long rear.

The last auto in the show caps a career that began with electric racers and an early hybrid. It is an experimental “Type 911 GT3R Hybrid Race Car” that contains a flywheel spinning between 28,000 and 36,000 rpm, storing energy kinetically rather than electrochemically as a battery does. Eventually Porsche hopes to match the race car with a road version.

Borrowing from an earlier curator, NCMA director Larry Wheeler described the Porsches as “hollow sculptures.” Nevertheless, through the decades the most important changes in the cars necessarily took place under the metal skins. For the more mechanically-minded, wall cards and the imposing catalogue provide details on the motors (always mounted in back), suspensions, cooling systems, and a good deal more.

“Porsche by Design” will be available through January 20 of next year. Its curator, Ken Gross, is an automotive journalist and former director of the Peterson Automotive Museum in Los Angeles. He has managed to spice up the show by including and discoursing on Steve McQueen’s Porsche Speedster and a gaudily and fantastically painted Porsche cabriolet owned by Janis Joplin.

So they’re not painted canvases.