Thomas de Hartmann, Orchestral Music of [….] (1895-1956), Elan Sicroff, piano (maker not identified), Lviv National Philharmonic Orchestra of Ukraine, Tian Hui Ng, cond., Concerto for piano and orchestra, Op. 61 (1939), Scherzo fantastique, Op. 25 (1929), Symphonie-Poème, No. 3, Op. 85 (1953); Nimbus Alliance NI 6429, © 2022, TT 70:59, $14.25 via Presto.

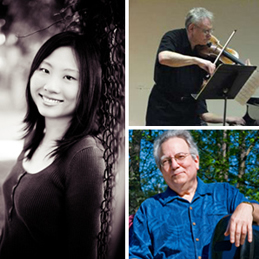

—–, Orchestral Music, Concierto Andaluz, Op. 81 (1949), Une Fête en Ukraine, Suite for Large Orchestra, Op. 62 (1940), Koliadky: Noëls ukrainiens, Op. 60 (1940), Symphonie-poème, No. 4, Op. 90 (1955), Bülent Evcil, flute, Lviv National Philharmonic Orchestra of Ukraine, Theodore Kuchar, cond., Toccata Classics TOCC 0633, © 2022, TT 65:00, $15.00 via Presto.

Dmitri Klebanov (1907-1987), Chamber Works by […], Piano Trio No. 2, (1958), String Quartets No. 4 (1946), & No. 5 (1965), ARC Ensemble (Artists of the Royal Conservatory [Toronto, Ont]), Erika Raum and Marie Bérard, violins,. Steven Dann, viola, Thomas Wiebe, ‘cello, Kevin Ahfat, piano (maker not identified), Chandos CHAN 20231, © 2021, TT 73:20, $14.25 via Presto.

Vsevolod Zaderatsky (1891-1953), 24 Préludes and Fugues (1937-39; the dates of his incarceration; his mother managed to get him released), Jascha Nemtsov (b. 1963), piano, (maker unspecified, perhaps a Hamburg Steinway?) Hänssler Profil PH 10528, © 2015, 2 CDs: TT 130:22, # 1 65:32, # 2 64:48, $25.76, via Presto; it is out of stock there, & may be out of print; I got my copy from Berkshire Record Outlet, now based in Albany, NY, which sells remainders & overstocks.

Most, if not all, of these CDs are first recordings of their works (only those of the first listed one are not so described); their scores were not published until very recently. I waited a long time to get the last of them, of which I had been aware for several years; it was composed during the composer’s incarceration by the Soviet government in a Siberian Gulag, written on a stack of telegram forms that an empathetic guard gave him (the accompanying booklet’s cover shows an example). It is the earliest of the modern sets (Shostakovich’s was composed in 1950-51, over a decade later) that follow the pattern/sequence of JSB’s ‘Great 48’ and is amazing. The composer ended his days in Lviv, so there’s an interconnection. The pianist, who performed the live world première at the Shostakovich Festival in Saxony in 2015 (this recording was made just after that, on 6-10 July, and the Festival and the composer’s son, Laurent, are thanked, so the takes may have originated there?), was born in Siberia, and now lives in Weimar; the YouTube video in the link for him has some samples from this CD.

Hartmann, a member of a Russian aristocratic family that lived in northern Ukraine, is experiencing a sudden interest in his music, that was initiated by the pianist Sicroff, who now lives in this area, although I have not yet met him; on the other hand, I know the conductor relatively well; he is the conductor of the Pioneer Valley Symphony Orchestra, and a professor at Mt. Holyoke College. After the death of his father when he was 9, Hartmann went to St. Petersburg to the military academy, whose director recognized his talent for music and allowed him to study it along with his training; he began studying at age 11 under Anton Arensky, who was then the director of the Imperial Chapel. After Arensky’s death, Hartmann studied with Taneieff (= Taneyev), and got his diploma from the Conservatory in 1904. Tsar Nicolas II heard his ballet La Fleurette Rouge; this led to the deferring of his military service, which led him to study with Felix Motil in Munich, where he met and became a close friend of the painter Wassily Kandinski (a work by him adorns the cover of the CD’s accompanying booklet; see my 5-part article about synesthesia that discusses him) that lasted until his death in 1944.

In 1916, he met George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff (1876/7-1949), an encounter that led to a long affiliation (until 1929, when Gurdjieff severed all connections with everyone) that led them to Tiflis (= Tbilisi), where he was reunited with his friend Nicolas Tcherepnin (1899-1977), who invited him to take over the composition class. The Hartmanns (he married twice, both times to an Olga; both died in Paris, where they lived from c.1930, and had hidden during WWII) immigrated to NYC in 1950. The booklets accompanying both CDs have excellent bios by the same author, John Mangan, but details differ, as do their accompanying period photos (except for one, but it’s clipped on the cover of the second listed); they are more numerous in the first listed.

The music and its performances are all excellent on both. They complement each other without any duplication – a rare occurrence; it’s almost as if it had been planned that way. It’s all melodic, smooth-flowing, and pleasing, growing generically, genuinely, and intuitively from late-Romantic music – and culturally too: there are lots of Russian Orthodox cathedral bell sounds in the 3rd and 4th movements of the piano concerto, and in the Radoniza of the Symphonie-Poème, No. 3, and are the very inspiration of Koliadky and Une fête en Ukraine that uses French names of Baroque dances as the titles of most of its 11 movements that follow a long Ouverture – without any bombast (in spite of the prominent presence of a lot of percussion instruments and some trumpets in some of the works, including the flute concerto, but that’s a different culture), pretension, or artificial excessive, over-the-top Wagnerian gestures, but at the same time very modern without excessive dissonance. The second listed CD also has notes for the works entitled: “Thomas de Hartmann’s Ukrainian Roots,” by Evan A. MacCarthy, whom I have not met. It is all very beautiful, generally calm, and lovely, well worth being more often heard! The horrendous history of the 20th century is likely the only explanation/reason that they have not been heard or known until now, and we can thank our lucky stars that their manuscripts survived!

The Klebanov is a change of pace because it’s chamber music, with standard forms/formats; it opens strikingly, however, with some very familiar music in the first movement: the “Carol of the Bells,” whose real name is Shchedryk (= Little Swallow), a melody by Mykola Leontovych, dedicatee of the tightly built/constructed Quartet No. 4, composed in 1904, that uses traditional Ukrainian tunes, and is the shortest work of the 3; this melody is often erroneously said to be Russian. His music simply was not performed because of the Soviet government’s suppression of Jewish culture, which fluctuated up and down over the years. There was also a period in the 1930s known as the “Executed Renaissance,” during which some 30 thousand members of the intelligentsia were simply massacred and some 3.5 million rural people were starved to death, a genocide known as the “Holodomor.”

Klebanov was among the over 150k Jewish refugees evacuated in 1941 to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, where he taught, and composed music for theatre and films, including co-writing the soundtrack of Battle for Our Soviet Ukraine (1943). Simon Wynberg, Artistic Director of the ARC Ensemble, wrote the excellent bios and program notes in the accompanying booklet. The ARC Ensemble’s performance of this engaging, gorgeous, essentially late-Romantic music is stellar; one wonders what in it offended the Soviet officials to justify its banishment. The program is organized chronologically; the music thus shows its increasingly more modern style, but without much dissonance; it is evenly balanced, with the trio, which has some bell-like sounds in it, its center.