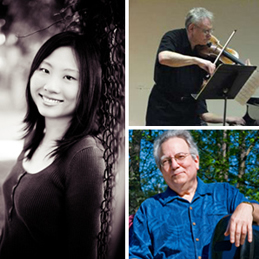

The Ciompi Quartet Presents series, held in the acoustical and visual jewel of Kirby Horton Hall, has been a welcome addition to the cultural desert of summer. The venue is the ideal size for the intimacy of chamber music, while all the exposed timberwork and extensive windows, opening onto the vistas of Sarah P. Duke Gardens, combine for a feast for the other senses. This final concert was a collaboration between Duke University, in the form of Ciompi Quartet’s cellist Fred Raimi. and violinist Richard Luby and pianist Clara Yang from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The program was a choice pairing of two duo sonatas for string instruments and keyboard with one of the greatest twentieth century piano trios.

Beethoven’s Sonata in D for violin and piano, Op. 12, No. 1, second only to his “Kreutzer” Sonata, Op. 47, is among my favorites. It was composed in 1787 and was dedicated to Antonio Salieri. The opening Allegro con brio is by turns playful and stormy with no lack of verve. The second movement is a gentle, flowing set of variations leading to an exuberant and rollicking Rondo. Both instruments are treated equally. Richard Luby’s articulation and intonation were excellent. Clara Yang’s “chops” were simply breathtaking throughout the concert. The fireworks between the two during the finale were spectacular.

The specter of Joseph Stalin haunted the two Russian works from the darkest days of the Soviet era. Stalin was the evilest music critic who ever held sway! Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953) and Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-75) show two possible reactions to Stalin’s threat of midnight one-way trips into the gulags or death.

Prokofiev by and large accommodated his compositions to “Socialist Realism.” His Sonata in C for cello and piano, Op. 119, composed in the spring of 1949, is a good example. Despite Stalin’s crackdown, it is escapist being optimistic with carefree light singing lines in all three movements. Raimi played with a beautiful tone ranging from a deep, rich baritone to a tightly focused tenor. His intonation was immaculate while his numerous and varied pizzcati were delightful. Yang’s pianism was astounding.

While Shostakovich composed some “safe” stuff for contemporary performance, his significant works were consigned to his desk drawers to be brought out in better times. After Shostakovich’s very public condemnation for his opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, the composer kept a suitcase packed by the door in case the secret police came. Shostakovich was very sensitive and held close friendships very dear. His closest friend, Ivan Sollertinsky had died suddenly at the age of 41 from a heart attack. The Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 was composed in 1944 and dedicated to his friend’s memory. It is in four movements. The first mixes an elegiac mood with somewhat more cheerful reminiscences while the second is a vigorous peasant dance with a waltz-like trio section. The third is a mournful passacaglia introduced by dark piano chords, followed by the violin and the cello in music of great vehemence. The last movement is dominated by a Jewish dance of Death like some macabre klezmer band. This reflects the composer’s horror of the Nazi Holocaust and Stalin’s anti-Semitism. This was Shostakovich’s first use of Jewish music in its own right and to demonstrate his identification with victims of persecution. The dance ends with an air of mourning.

Yang, Luby, and Raimi conjured a performance of great intensity and deep commitment. The eerie opening was aptly haunting with very few slight blemishes in Raimi’s solo as he spun out Shostakovich’s extreme high, glassy harmonics. Luby soon joined with equally ghostly, muted strings quickly joined by Yang’s hushed piano. Their second movement was a wild hoe-down, a brash foot stomper. The musicians brought out the full horror the composer meant his nightmarish Largo to convey, and this quality was present in spades violent musical imagery of the finale.