The cerebral work of Zachary Tate Porter is now on view in “Groundwork” at MoNA Gallery in the NoDa arts district. The artist is currently producing works rooted in architecture, cartography, and archaeology, employing line and composition to measure and explore imagined landscapes.

Porter’s abilities as a draftsman are apparent although he is uninterested in replicating the world as it exists. Trained as an architect, Porter is concerned with site preparation, specifically the way land is measured, consecrated, marked, and deemed worthy of habitation. He is also interested in challenging traditional methods of architectural representation by focusing more on the land that becomes impacted than the building that sits upon it. His artwork documents human interaction with the land without commenting on how it should be carried out.

MoNA Gallery, with its whitewashed vertical-paneled walls and aged concrete floors, provides an excellent backdrop for the body of work, all of which has a very handmade quality and runs the gamut from paintings coated in thick resin to mixed media pieces that reveal Porter’s fondness for collage. The work is iterative, a record of processes: themes, colors, and composition are thought over, erased, and redrawn. In fact, many appear unfinished – as if they were taken from the studio in mid-thought, mid-scribble. As the relationship between architecture and land is an endless process of control and relenting, so too is Porter’s work.

Porter is an architecture student at Georgia Tech, developing a Ph.D. thesis that explores site preparation and the initial conversation with the land intended for architectural transformation and habitation. Porter was born and raised in Matthews, NC, before attending the UNC Charlotte School of Architecture, receiving both his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Architecture degrees. His first exhibition of artworks took place last fall in the Central Piedmont Community College Pease Gallery. During a lecture accompanying the exhibition, he said he is “interested in a certain kind of ambiguity that takes hold of the viewer’s imagination and won’t let it go.” It is his reasoning for placing so many symbols, numbers, and cutout words in his paintings; he hopes viewers will draw their own experiences and connect on their own the “dots” formed by these strategically placed elements. Encouraging this thoughtfulness enables the viewer to take ownership of the work and enjoy it in a way that no one else is capable of. Porter is considerate in this way, and the influence of years in architecture school becomes clear for a moment: just as each user’s experience of an architectural space is different, these “spaces” on canvas and paper created by Porter are occupiable and affective in different ways to each viewer.

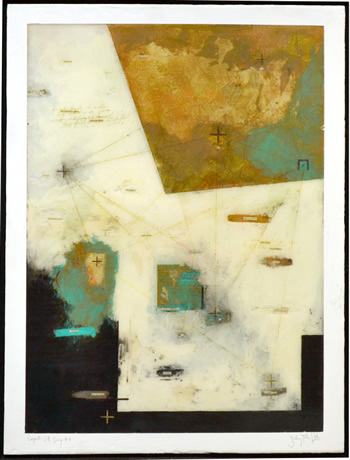

Porter groups his work in series, each with strongly differentiated visual components, though all record imagined landscapes or objects tied to them. Especially striking are the Prospective Site Surveys, five larger pieces in white, black, gold, and turquoise. The colors are contained within angular forms floating and layering over one another, with color density ranging from opaque to thin and uneven. They measure imaginary sites and are replete with “surveyors’ lines,” connecting objects in the field, and symbols like crosses and crescents which populate the surface along with collaged words, phrases, and strings of numbers. Like the work of renowned artist Guillermo Kuitca, self-described as using the image of a map “to get lost, not to get oriented,” Porter’s cartographic explorations are abstracted and embellished beyond the point of assimilation.

The color is vibrant, balanced, and harmonious in the Ground Studies series. Brushed, layered hues range from pale gray to bright red, with deep gold, burgundy, navy, lemon, and lavender. The application of color is soft and transcends elements of composition, providing a celestial, otherworldly backdrop to a crisp grid of lines that is drawn atop it. Additional lines overlap the grid in seemingly random fashion, connecting characters and boundaries that would exist on a property survey, such as fence posts, trees, etc. The layering of these vectors begins to suggest a third dimension, forms that appear to be floating in the celestial clouds of color beyond. The points where they connect are labeled with small phrases or numbers cut from books (like those found in the Prospective Site Surveys series), which lay down a vague path that allows the viewer to draw meaning. In these Ground Studies, as in architecture, the organic is at odds with the measured and manmade, but like any well-designed building the result is pleasant and graceful, celebratory of the inherent contrast.

This body of work began as a complement to academic studies but grew as the artist became more interested in visual explorations of themes as a component to written exploration. Porter is right to travel this road and audiences should be prepared for further exploration. Based on the variety of work here, any viewer should be able to find a piece that satisfies them.

The exhibition continues through January 31. For details, see the sidebar.