Tim Artz as Mat Burke in “Agatha Christie”. Photo credit: Camille Mahs / Camille’s World Photography

WAKE FOREST, NC – In 1922, Eugene O’Neill’s pungent waterfront drama Anna Christie earned the playwright the second of four Pulitzers he would ultimately collect, the most given to any American playwright to date. Just over a decade later, O’Neill would be named a Nobel laureate – well before he wrote the epic works he’s now best known for: The Iceman Cometh, A Moon for the Misbegotten, and Long Day’s Journey into Night.

Still, most theatrical revivals stand or fall on one issue: what, if anything, a script from yesteryear has to say to us in the present tense. There’s a bit of cultural whiplash in store when you place the scuzzy denizens in O’Neill’s script, set on a coal barge and in a seedy bar on New York’s disreputable industrial waterfront, circa 1921, alongside well-heeled patrons of the arts in the tony, still-developing entertainment and nightlife district of Wake Forest – or at least, there should be.

But if the minimal set and tidy at times costumes in Firebox Theatre’s production leave much of the squalor only minimally visible in that world, the acting underscores the differences between the two.

It’s tempting to give dialect coach Danica Jackson from NC State University equal billing with director Zachary Roberts, given the distinctive, foregrounded accents so central to O’Neill’s text. If actor Tim Artz’s Irish brogue were any thicker as the rescued seaman Mat, you could slice and butter it like soda bread. The musicality in veteran Michael Foley’s Scandinavian tongue as Chris, the aging, moody patriarch, gives a sometimes mournful lilt to his often broken English.

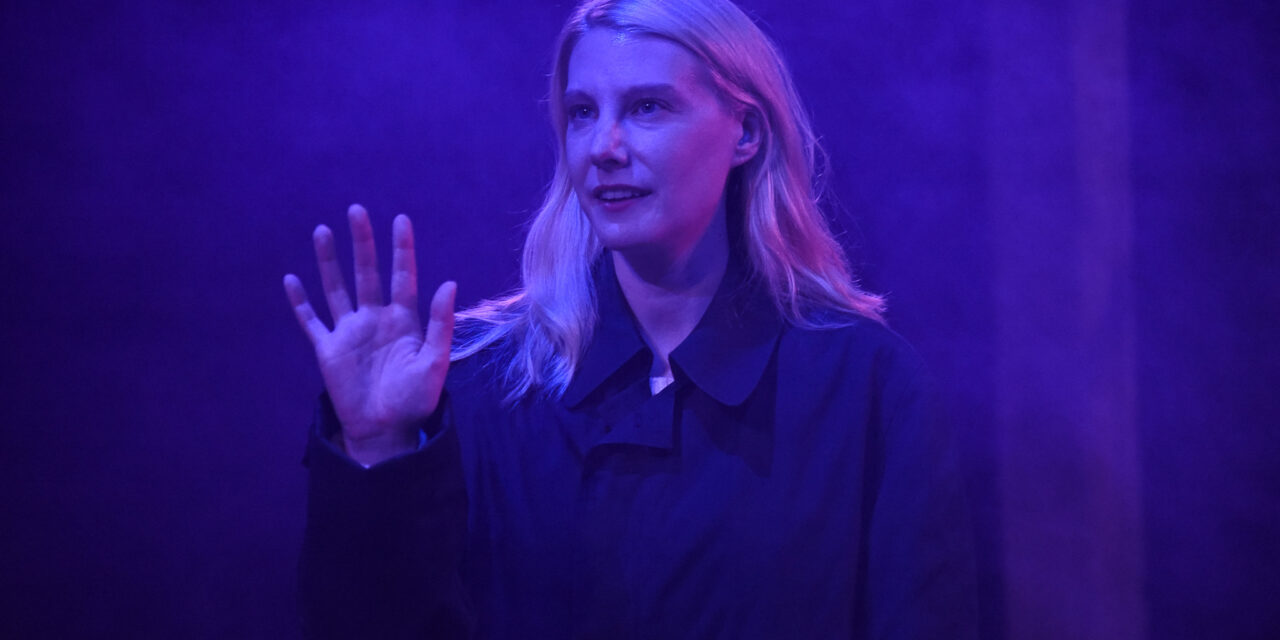

But the sense of ensemble that permeates the principal characters – those above plus Hilary Edwards’ nuanced work in the title role – brings their time closest to ours, in a way that should provide us no comfort whatsoever.

For Anna has been a sex worker; 20 years old, on her last legs after a hospital stay, and seeking sanctuary from her absentee father, Chris. After her mother died fifteen years ago, Chris unwisely left her in the care of distant relatives on a farm in Minnesota and continued working as a sailor. There, she was abused, treated “worse than they’d dare treat a hired girl,” escaping only after being raped by her youngest cousin at age 16. “After that, I hated ’em so, I’d killed ’em all if I’d stayed,” she tells a frowsy Marthy (a robust Angela Skinner), a woman of the docks who’s been Chris’s current partner.

Though the only refuge her father can offer is his captain’s cabin on the deck of a coal barge, life on the sea more than revitalizes her. “I feel clean, somehow,” she tells Chris, “happier than I ever been anywhere before!” Still, a brooding Chris reminds her that the shoreline routes the barge takes isn’t the real sea. “You only see nice part,” he says. Throughout, he harbors the fear that the “davil (devil) sea” will claim her as he thinks it has already him.

Those fears are realized when his crew brings aboard Mat, a survivor from a shipwreck, and he and Anna swiftly fall in love.

Then entirely different, but verifiably mortal, fears come into play once Mat and Chris learn the truth Anna has kept hidden about her past.

And here is where the mirror comes out that reflects their time, one century ago, in ours, and vice versa. In a word, the sight is ghastly.

In 2019, the most recent year available for statistics, 84 women died at the hands of an intimate partner in North Carolina. That year, some 59,000 victims reported incidents of domestic violence across this state.

We cite these facts here because the venom and velocity with which Mat responds when he learns of Anna’s past place her life in immediate danger. We should also note that the intensity of the physical acting Taylor has achieved with his actors may easily trigger audience members who have experienced domestic violence themselves. Artz’s harrowing performance as Mat was easily the strongest work the region’s seen from him to date.

As was the case a hundred years ago, there remains no shortage of men who believe it their prerogative to lay hands on a woman as if she “was a piece of furniture,” as Anna shouts in a mid-show showdown with Mat and Chris. “You was going on as if one of you had got to own me. But nobody owns me, see—’cepting myself!”

If these were radical words for a woman in 1920, given the ongoing war on contraception in the U.S., they remain unacceptable for many in 2024.

The monstrous self-pity and self-righteousness with which Mat initially receives the news of Anna’s plight places no act of retribution beyond the possible.

And when all three of these characters grasp at the slender straws of an ending happier than one involving multiple homicides – at least for now – it occurs to me that the father of modern American drama chose the wrong name for this story of a woman’s subjugation, one that is only continuing to unfold as the last scene ends.

It should have been titled No Exit, instead.

Firebox Theatre’s Anna Christie continues through Sunday, June 2.