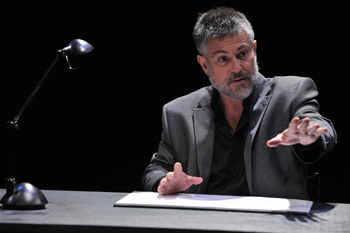

Burning Coal Theatre Company is reviving a show they first produced ten years ago, St. Nicholas. Jerome Davis, one of the founders of the company and an experienced performer, is featured as the only actor in the production. The character is an alcoholic theatre critic working in Ireland who thrives off the power he derives from deciding the fates of shows. After reviewing a show, the critic follows the young lead actress as the play moves to London. During his stay in London he encounters vampires and begins to work for them. The arrangement leads him to having an opportunity to find the young actress and have her alone. Davis takes the audience on a haunting tale of discovering what it means to have a conscience.

By the end of the piece, the critic exposes moral truths and poses challenging questions. While Davis met the challenge well, I had trouble forgiving the character enough to heed his advice. The critic asks, “Isn’t wanting a conscience the same as having one?” He poses this thought in reference to William, the vampire, but I can’t help but relate it back to the critic instead. At the points where the critic needed a conscience, he found that he really didn’t have much of one. After the years of slogging down alcohol and neglecting his family, the critic continually showed a lack of care for others. This play can be interpreted in many ways with no way necessarily being wrong. While the vampires offer a contrast to humans, the audience finds that the critic is lacking a humanly conscience – like the vampires. What a terrifying thing to realize you don’t have a conscience and that you are comparable to a creature!

I’m not sure that the critic ever felt remorseful for his acts, though. Perhaps this is why I had such a hard time connecting with his character; his selfish acts made it hard for me to care. While the story – and Davis – were intriguing, I did not like the character. Thus, I found it hard to appreciate the ending remarks that could have offered a great deal of “food for thought.”

I fully respect Davis’s efforts to engage an audience for nearly two hours. The final minutes concluded that whoever in the audience is in love is a symbol of hope for the rest of us that we may, too, be that happy one day. While it is a beautiful sentiment, I have a difficult time seeing how the critic came to this conclusion after listening to all the choices he made. The character’s alienation and abandonment of his family and then the stalking of a young woman does not make me want to believe that he could show me a moral. Playwright Conor McPherson’s string of events leading up to the denouncement made me question how the critic could come to these conclusions on his own. Davis did an excellent job with what he was given, but I would prefer to see the same meaning come out of a story that wasn’t so distant.

Burning Coal’s production met the challenges of the piece very well. The minimalist set and lighting did not detract from the ever-evolving story told in first person. The fluidity of the piece was upheld on all accounts – from the acting to the technical elements. While I struggle to heed advice from an unsavory character, it is a testament to the piece that I am still wading through the heavy layers and nuances. This production definitely offers unique interpretations for all.

St. Nicholas continues through November 21. For details, see our calendar.

*The author is a member of our ongoing internship program at Meredith College.