The 2007 installment of the Spoleto Festival USA got underway on May 25 and continues through June 10. It’s not the longest “summer” offering in our part of the country, but it is easily the most complex, presenting a vast array of events in every legitimate branch of the performing arts. For six years, CVNC has provided extensive coverage of Spoleto USA, generally however limited to the second week of the festival. This year, the happy coincidence of the annual meeting of the Music Critics Association of North America prompted more than our customary interest in Charleston, and in addition we have representation in the last week of the festival, too, so our readers will get a larger-than-usual dose.

In the second week, we sampled chamber music, opera, an orchestral concert, and a choral program — discussions of Kurt Weill’s Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny), a program devoted to works by Ravel and Brahms played by the “Ginn Resorts Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra,” and a late-afternoon concert by the Women of the Westminster Choir follow below.

The “Bank of America Chamber Music” series is coordinated by pianist Charles Wadsworth, who is known as one of the great raconteurs of the business. It’s doubtless been helpful too that his other half is head of Young Concert Artists, Inc., through which he’s had ready access to some of the very brightest and best talent. The concerts in this series are being given this season in the Dock Street Theatre, a building that looks ancient but was built in 1936 and that is scheduled for a major renovation starting in July. (If the renovation involves making the seats more commodious and comfortable, ’twill be tantamount to money well spent!) Eleven different programs are each offered three times. The works to be presented are not published in advance but are posted on a chalkboard at the front of the hall. The artists are all major figures in the music world, folks one would be thrilled to hear back home, with the local orchestra, or on the local chamber music series, for sure.

On the afternoon of May 30, following a brief introduction by Wadsworth, the concert got underway with the second performance of a new version of Debussy’s Première Rhapsodie, originally for clarinet and piano and later orchestrated by the composer. (The first performance took place just hours before, at the 11 a.m. reading of this Chamber Music IV concert.) It featured Todd Palmer, clarinet, Tara Helen O’Connor, flute, the St. Lawrence String Quartet (which is the “Arthur and Holly Magill Quartet in Residence” at the festival), Edward Allman, bass (of the Charleston Symphony Orchestra), and Catrin Finch, harp. The arrangement was by Palmer himself, and he has handsomely pulled the proverbial rabbit from the hat by shrinking Debussy’s large version to a lean, richly-textured chamber work of considerable appeal. The performance was superb in nearly every respect although, truth to tell, violinist Geoff Nuttall’s kineticism, given greater prominence than might otherwise have been the case by his conspicuous gray shoes, adorned with straps and buckles, was something of a distraction.

Soprano Courtenay Budd performed lullabies by Dvorák (“Ukolébavka”) and arranged by Canteloube (“Bresairola”), from her new CD, Sleep Is Behind the Door, being sold as a benefit for disaster relief. The former was accompanied with keen insight and feeling by Wadsworth; the latter, in an arrangement by Fecteau, by O’Connor, Palmer, violinist Daniel Phillips (of the Orion String Quartet), and Christopher Costanza, cello (of the SLSQ). The Dvorák, new to this listener, is a winner, and so, too, is the familiar and much-loved Song of the Auvergne, made popular for a generation of music lovers by Madeleine Grey. Budd did these songs great justice, winning enthusiastic applause from the near-capacity audience.

The SLSQ returned to perform Schumann’s Second String Quartet, in F, Op. 41/2, a work that grows on listeners who permit its many delights to make their marks. The performance was typical of the ensemble’s readings, which is to say animated, precise, incisive, finely balanced, and keenly felt.

The concert ended with Palmer’s recent arrangement of Weber’s “Invitation to the Dance,” originally for piano solo but perhaps better known in Berlioz’s brilliant orchestration, to which this chamber reduction seemed more than a little indebted. The players were O’Connor (doubling on piccolo), Palmer, the SLSQ, Allman, and Finch. For reasons not altogether clear, the work emerged four-square, with excessive rhythmic emphasis, and thus seemed atypically earthbound. That this view was not shared by the majority of the audience was clear from the tremendous outpouring of applause at the end of the performance.

Wadsworth is the glue that binds these programs and makes them, for many patrons, incessant delights. On this occasion, his between-the-acts banter included serious commentary on his discovery that grits, ubiquitous in the Lowcounty, are responsible for some lessening of the effects of global warming because, he averred, it’s been much nicer than usual in Charleston this time around….

Chamber Music V, heard on the afternoon of June 1, began with soprano Courtenay Budd, cellist Andrés Díaz, and pianist Charles Wadsworth performing “Tone sanft,” from Handel’s Alexander’s Feast, and “Sono guerriera ardita,” an aria from one of Alessandro Scarlatti’s operas. The two brief selections made an attractive pair, and the singing was radiant — a quality that carried over to the second offering of the day, Dvorák’s Four Romantic Pieces, which glowed in readings by violinist Daniel Phillips and pianist Wendy Chen. These are, as Wadsworth had explained, rarely heard, which is hard to fathom, given the appeal of the music and its searching emotional depth; at the end, speaking specifically of the third movement, he noted, too, that “This is what it’s all about” — a truism if ever there was one.

The concert ended with a performance of Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 1, in B-Flat, D.898, given by violinist Chee-Yun and Díaz and Chen. It was for the most part an admirable reading, although the violinist’s intonation and/or ensemble slipped a bit in the slow movement and the pianist was often so much less than forceful that she seemed at times to be an accompanist rather than an equal artistic partner. This cast some new light on the familiar music, allowing fuller than usual concentration on the string parts, which was not altogether problematic: the playing was often delicate, refined, and engaging, and the overall result was frequently spellbinding — even if it wasn’t quite spellbinding enough to discourage applause between the movements…. All that said, the outpouring of appreciation at the conclusion of the piece was immediate and protracted.

(The M.C.’s introductory comments on this occasion, which might have been subtitled “Dropping In,” dealt with less than heartwarming encounters with birds in Charleston and Rome…. And in the interest of equal time, I must note that Chee-Yun wore sequin-bedecked high heel shoes but managed to keep her feet at all times within 2″ of the stage…)

Our third concert in the Chamber Music series (“Chamber Music VI”) brought forth C.P.E. Bach’s Concerto in D minor, here performed by flutist Tara Helen O’Connor with violinists Daniel Phillips and Scott St. John, violist Lesley Robertson, cellist Christopher Costanza, bassist Edward Allman, and harpsichordist Charles Wadsworth, whose banter during this program reached new heights of unrestrained silliness. Fortunately, the Concerto itself was something wondrous to behold and hear, and O’Connor proved a dazzling soloist of the highest virtuosity. The work is at once challenging and lovely, and it’s a fact that if the artists were paid by the note, then the accounts would have been emptied to fund just the flutist. There was an uproar at the end that was, in this instance, richly deserved.

A comparable reception was accorded Brahms’ String Sextet No. 2, in G, Op. 36, as played by the St. Lawrence String Quartet — violinists St. John and Geoff Nuttall plus Robertson and Costanza — and Phillips, who here switched to viola, and cellist Edward Arron, of the Caramoor Virtuosi. These six artists worked together like a well-oiled machine, and the results were impressive. Of course, one can hardly go wrong with Brahms, so this was a lovely way to end our sampling of the chamber music offerings in the Dock Street Theatre during this year’s Spoleto Festival USA.

On the evening of May 31, in the Sottile Theatre, Emmanuel Villaume led the Festival Orchestra in a brief, intermission-less concert consisting of Ravel’s Ma Mère l’oye (Mother Goose) Suite and Brahms’ Symphony No. 4. (The published roster of this orchestra lists many more players than took part in this program, which involved only four basses and six cellos as the ensemble’s sonic floor.) The hall is an attractive alternative to other venues that have hosted the orchestra in previous seasons, but it is not ideal, as perceptive listeners to the first half of the Ravel surely noted, to their consternation, when a nearby truck’s back-up alarm intruded on the ethereal quiet of the music. The playing was nonetheless exquisite, and those low strings sounded convincingly Gallic throughout. The woodwinds projected a more “international” (as opposed to French) tone. It was readily apparent from our vantage point in the hall that the young musicians were giving their utmost and having a grand and glorious time, and the audience seemed to relish every minute of the reading.

The Brahms, too, received an elegant, polished interpretation, although the third movement was taken at such a rapid pace that at times it seemed to allow no opportunity for reflection. (On the other hand, given the slick new turbo-charged sports car that the Festival Orchestra is, and given its Maître’s evident delight in showing it off, one can hardly complain that the speed wasn’t limited to 55 m.p.h.!)

The other three movements more than compensated for any reservations one might have had. There was superb playing by individuals, sections, and the entire ensemble, with particularly praiseworthy work from the concertmaster, the solo flute, oboe, and clarinet, the timpanist, and the horns. The crowd knew it had heard something very special, indeed, and gave the artists an enthusiastic reception, punctuated with cheers and bravoes.

One must, however, wonder why, at festival prices, the program lasted a mere 60 minutes….

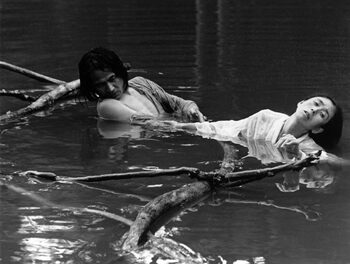

Someone said that The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (1930), by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht, was the Festival’s pièce de résistance, adding that he wasn’t sure if it meant that this is the piece to resist…. During a performance on the evening of June 1, given in a less-than-full Sottile Theatre, it was clear that this is a major work of art that in a sense encompasses all the goals and objectives of Spoleto USA, inasmuch as it weaves together strands of theatre, dance, and of course music — both opera and cabaret — echoing the past and hinting at the future. Mahagonny was sung in German by a remarkably strong and convincing cast that included some well-known and much-admired artists. The stars of the show were the men, headed by tenor Richard Brunner (as Jimmy Mahoney), whose singing and acting were consistently strong. His sidekicks included tenor Dennis Petersen (Jakob Schmidt and Toby Higgins), baritone John Fanning (Moneybags Billy), and bass Kirk Eichelberger (Alaska Wolf Joe). Tenor Beauregard Palmer (Fatty) and baritone Timothy Nolen (Trinity Moses) plus 20 men from the Westminster Choir, prepared by Andrew Megill, rounded out the roster of male artists. The distaff side was headed by sopranos Tammy Hensrud (Jenny) and Karen Huffstoft (Leokadja Begbick), with sopranos Maija Lisa Currie, Ariana Watt, and Clara Rottsolk, and mezzo-sopranos Hilerie Klein Rensi, Ivy Gaibel, and Teresa S. Herold, as the girls of Mahagonny. Emmanuel Villaume conducted the Festival Orchestra, and the production was directed by Patrice Caurier and Moshe Leiser. The sets (by Christian Fenouillat) and costumes (mostly by Agostino Cavalca) were constructed by Opéra de Lausanne, and it is likely that the lighting, by Christophe Forey, was established in Lausanne, too.

This preposterous anti-capitalist tale is told in a series of vignettes or tableaux, richly enhanced by some of Weill’s most engaging music. Although the work was banned by the Nazis — it’s easy enough to see why… — and it waited till 1979 for its first Metropolitan Opera production, it has achieved a remarkable degree of fame and popularity, too, in its relatively short life. The plot centers on a bunch of ne’er-do-wells, outlaws, and misfits who set up and inhabit the town of Mahagonny, where the motto is “do your own thing — as long as you have money to pay for it” and where, as viewers discover at the end, the greatest sin is running out of cash. The finale comes across as a bit contrived, but perhaps it’s no more so, in its own way, than the last little section of Don Giovanni.

Mahagonny and of course Weill and Brecht, too, surely had profound impacts on both music and theatre in America and elsewhere; as Fernando Rivas has written (in Charleston’s arts-rich City Paper), the score’s influence can be seen in other quasi-crossover scores ranging from Candide to Sweeny Todd and beyond. It is pretty much non-stop action as the tale unfolds, and the bright, brilliantly colored costumes, the amusing sets, and the high levels of interaction among the protagonists make for a brisk and refreshing evening in the theatre that surely appealed equally to opera and Broadway fans. The singing ranged from wonderful to good with, as previously noted, the men fairly consistently out-singing the women (and not only because there were more of them). Brunner was a tower of strength and agility, and his pals were uniformly good, with the low voices particularly rich. (Fanning first attracted our attention in last year’s Canadian Opera Company Ring.) Hensrud was dramatically effective as Jenny; Huffstodt looked convincing enough as the Widow Begbick but often seemed to be in vocal distress that, in turn, affected both her diction and her tone quality. Between the bracing orchestral introduction and the work’s finale, the orchestra breathes life into every number, at times with substantial stage bands that are integrated into Mahagonny‘s inherent theatricality. Villaume and his instrumentalists thus merit consideration at every step alongside the principals and choruses, and it is appropriate that he (and they) shared fully in the ovation at the end of the show. Bravo!

The women of the Westminster Choir got more or less equal time for a lovely program given twice and heard on the afternoon of June 2 in St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church. “Les Angélus,” according to its creator, conductor Joe Miller, “focuse[d] on the relationship between the conscious and unconscious worlds.” It did so by interleaving selections from Shostakovich’s Songs from Jewish Folk Poetry, Op. 79 — songs that deal with people who are, variously, oppressed — with other pieces, many of which have angelic themes or connotations. Thus the program began with the 15 singers performing ancient chants; the lineup then included works by David MacIntyre, Chesnokov, Debussy (arranged by Clytus Gottwald), Chen Yi, Joan Szymko, Nancy Telfer, and Z. Randall Stroope. All these composers except Shostakovich, Chesnokov, and Debussy are in the land of the living, none is older than 57, and three of them are women; this made for a fascinating and remarkable program that was splendidly sung by this outstanding ensemble. The Shostakovich songs were accompanied by pianist Stephen Hopkins and featured tenor soloist Adam Klein, who was amazing in every respect in solos, duets, and performances with the choir. Along the way, four fine soloists from the choir — Irene Snyder, Katie Gronick, Sue Gerace, and Lisa Juzwak — were also heard; like their male colleagues in the opera, they gave proof positive that the next generation of singers will likely be a fine one and finely prepared, too, to enrich our lives with music. (For reasons not altogether clear, one number of the 11-part Shostakovich cycle was omitted.)

Chen’s four Chinese Mountain Songs were special delights; the chorus rendered these arrangements with great insight and understanding. They and several other numbers were sung from various places in the balcony of the small, old (1836) church; indeed, the choir was everywhere during the program, singing from the foyer, from above, from around the outer walls on the main floor, and from the front of the church, too. There may have been a shade too much movement, but at least it kept the capacity crowd on its toes, and it also helped minimize the effects of the many seats that would otherwise have had seriously obstructed views of the front of the church.

Members of the Music Critics Association of North America (MCANA) were cordially received by Spoleto Festival USA staff, and along the way many pleasing and helpful amenities were provided. These included a panel discussion featuring Pascal Dusapin, the composer of Faustus, the Last Night, and John Kennedy, the conductor of that opera (which is being reviewed by our colleague William Thomas Walker); music critic Jean-Jacques Van Vlasselaer (of Le Droit), served as the moderator and ad hoc interpreter. At a breakfast at Spoleto headquarters, Festival General Director Nigel Redden and Music Director Emmanuel Villaume offered brief remarks; Redden also sat (although the operative word is “stood”) for an interview with critic Susan Elliott (of MusicalAmerica.com/) during which questions from conference attendees were posed.

Later during the MCANA’s gathering, Steven Brown (of The Charlotte Observer) introduced a presentation on non-profit organizations and their financial forms and 990s, in particular, given by Chris Burgess of the College of Charleston. At the organization’s annual business meeting, it was announced that Tim Smith (of the Baltimore Sun) has been elected to a second two-year term as president of the MCANA. Day-to-day administration of the group remains in the skillful hands of Managing Director Robert Leininger.

A moving highlight of the 2007 Spoleto Festival was a tribute/memorial to founder Gian Carlo Menotti, who passed away in February, in Monte Carlo. This took place on May 31 at 11 a.m. in the College of Charleston’s Sottile Theatre and involved soprano Karen Huffstodt (who portrayed Leokadja Begbick in Mahagonny), the Spoleto Festival Orchestra, and conductors Marc Dana Williams, Villaume, and Kennedy leading music by Menotti (the Pavane from the Sebastian Suite, and “To this we’ve come,” from The Consul) and his life-long friend Samuel Barber (the famous Adagio, for strings, performed in the version created at the request of Toscanini). Artistic Director for Choral Activities Joseph Flummerfelt offered remarks about Menotti the man and artist, and the Honorable Joseph P. Riley, Jr., Mayor of Charleston, spoke of the joint effort that the Spoleto Festival USA represented and of its salutary and long-term impact on his city. (He was mayor at the time of the first edition of the Festival, in 1977, and he remains the mayor today.) The memorial concert proved powerfully moving as spats that once commanded headlines around the world were supplanted by the warm glow of thanks and praise for all the good wrought by the lengthy partnership of our distinguished composer with our gorgeous Southern city. The Adagio was particularly moving, and the music was played as a montage of black and white photos of Menotti from the Festival’s earliest days filled a screen at the back of the stage.

Our visit to Charleston, known as “The Holy City” due to its vast number of (in many cases huge) old churches, began with a rare inside look at preparations for a major Spoleto Festival USA event: thanks to an invitation from a member of the Charleston Symphony Orchestra Chorus, we sat in on a rehearsal of the chorus portions of Verdi’s Messa da Requiem, led by Joseph Flummerfelt, whose experience and command of the choral arts make him one of the grand masters of our time. Alas, we weren’t able to remain in South Carolina for the performance itself, but CVNC‘s continuing coverage will include a review of the Verdi and other remaining events by our colleagues William Thomas Walker and Jeffrey Rossman, so stay tuned!

Note: Spoleto Festival USA continues through June 10 in Charleston, SC.

Note: For all our reviews of Charleston events this year, linked from one page, click here.

Edited/corrected 6/7/07.