I have a problem. It is evident when you see me; it affects my every move, and it is one that I have had to come to grips with. It is a problem Nature has dealt me, and it has made me cautious. I am physically handicapped. If I must walk, I walk with a cane. When I can, I use a power chair. There are things that, even though I know I can do them, I just no longer attempt. It is a hard truth, and one I have learned to accept.

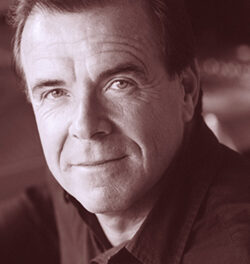

Sonny Kelly also has a “problem.” It has made him cautious, as well. It is a problem that makes him look at the world in a different fashion than I do. It is a problem Society has dealt him, and it affects his every move, even his every thought. It is a problem handed down to him by his mother and his father, and one he will have to instill in his children. Sonny is black. And in today’s society, even now, it makes him see the world differently than I do. It is a hard truth, but it is one he has accepted. It is one he has even embraced.

In a 75-minute monologue, Sonny sits us down to have The Talk. This performance is taking place at a new performance establishment in downtown Durham, The Fruit. Now, every child should have a parent sit him down and have “The Talk,” but the one I received from my parents is not the one that Sonny must give his sons, Sterling and Langston. My talk was about the birds and the bees. The Talk that Sonny must have with his son is about the blacks and the whites.

This is a monologue that began to take shape when Sonny realized it was time he had The Talk with Sterling. It was not a talk he wanted to have; it was one he knew he must have. In sum, it boiled down to this: be aware. Be aware that, even though there are many friends you will make that are white, there are those who will never be your friend. There are those who fear and hate you simply because of who you are. No, not even that – simply because of the color of your skin. You can see why Sonny did not want to have this talk with Sterling. It is a shame, a shame on society, that it is even necessary, in this day and age, to instill a caution into the life of a growing, thriving seven-year-old boy, to have to tell him that he must be on guard against an enemy he doesn’t even know, an enemy as real as any in a war. Sterling must learn to be aware that some whites – not all, certainly, but some – fear and hate him, and they make a concerted effort, every day, to exterminate or control him and his brothers and sisters.

There are too many examples of this to put into Sonny’s talk, but he tells us of a few. We learn of Emmett Till, a young boy who was on vacation with family members in Mississippi. Because two white men thought – that’s all it took, just the belief – that Emmett flirted with the wife of one of these men, they killed him for it. They beat him to death in the street and threw his body into the river. But what of that, you say? That it took place over fifty years ago? Then let’s turn our thoughts to this century. There was the case that became a national horror story in Florida. Trayvon Martin, a young black man heading home, was stalked and shot dead because a man named Zimmerman believed him to be a criminal. No proof. And no conviction. Zimmerman was found not guilty. And the case of Freddie Gray, shot and killed by policemen who say they believed he had a gun. Six officers were indicted; three had the charges against them dismissed, and the other three were found to be not guilty. How is a father to explain these injustices to his son? How is the Rule of Law to be understood and accepted by a small boy in the face of these travesties? Sonny had read, as an adolescent, Alex Haley’s Roots, and The Autobiography of Malcolm X. He knew the struggles, the daily fight for survival, for a place, for dignity in the eyes of society. The black man has known this for centuries and this knowledge has been passed down to every young man and woman. In the face of this cruelty, learn dignity. Learn integrity. Learn how to live the best life you can in the face of this enigma.

There is joy, nonetheless, in Sonny’s talk. There is the joy of fatherhood, of knowing that he is raising two stalwart and strong young boys. There is the joy of learning, from his father, how to work and earn and have dignity. Have pride in who you are and what you do. There is the joy of learning, from his mother, to “take your lessons,” educate yourself, learn the past so you can change the future; the joy of a father who raised him passionately, who called him “Boy Wonder,” who taught him dignity and grace in the face of adversity; the joy of learning that the truth will set you free; and the joy of learning how to use that truth to be free and to be a Black Man in the twenty-first century.

These are not truths that I did not know. I grew up knowing these truths. In my town, growing up, the Negroes lived, literally, on the other side of the tracks. This was a given. I learned it not so much from my mother, who was Canadian, and who looked on quizzically at the situation in a small Appalachian town. And not so much from my father, who was a Staff Sargent in the Army in World War II, and who had white and black men under his command. No, I learned my lessons from the People that this was “the way things are.” What was instilled in me was done indirectly, not like the lessons I learned in school. Indirectly, I was taught that Sonny’s Black Man was someone to be feared: that two or more black boys together might be a gang to be feared. No one told me this; it was seeped into me through my skin, by osmosis. Sonny’s Black Man was a danger. That was “the way things are.” Never mind that the black student, Mike, who sat next to me in English, was a better friend to me than most of the white boys I knew. Never mind that I was raised by a black nanny. Never mind that there were boys – happy, respectful boys – who walked up and down the streets of my neighborhood, making a living by selling gladiolas. Never mind that. Just remember “the way things are.”

Sonny knows that I was taught about the boogey man, but so was he. And the two are different. Sonny’s boogey man is real. Sonny’s boogey man is James Alex Fields, a white supremacist who drove his car into a crowd of protesters in Charlottesville and killed a woman – and injured another thirty people, besides. Sonny calls this an act of terrorism. It comes from the people with power and pistols; it’s an act of fear and rage at “those people’s” all-encompassing Blackness.

Sonny had his talk with Sterling. He told him that Sterling means “little star,” that it means one who is pure and thoroughly excellent. Sonny has given Sterling his power to be excellent, to have integrity. Sterling’s teacher told Sonny this, “Sterling has integrity.” Sonny wants for his boys what every parent wants for his or her children: he wants better. A better life than he has, maybe even one in which it is not necessary to keep looking over your shoulder. But today, Sonny told Sterling, “All I see is a little boy. I need you to be your best.”

The Talk is a thoroughly engaging and engrossing tale, sprung from the need to instill in a child the understanding and grace to see the world as it is and to have the courage to change it. It will teach you lessons you already know, but after you hear The Talk, you will know them in a different way.

The Talk is presented by StreetSigns in association with the UNC Department of Communication; the producers are StreetSigns and Bulldog Ensemble Theater of Durham with the aforementioned UNC department. The show runs through February 10 at The Fruit and then it moves to the Historic PlayMakers Theatre on the UNC campus for four performances, February 14-17. For more details on these performances, please view the sidebar.