Melodie Galloway is beginning her second season as Music Director of the Asheville Choral Society, and we can now see some of the similarities and differences between her leadership and that of Lenora Thom, who led the group for ten years ending with a most successful performance of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana in March 2010. The programming continues to be vibrant and challenging, with Rachmaninoff’s All-Night Vigil being the major work on Friday’s program. It is clear that Dr. Galloway plans to continue to program repertoire with multi-part harmony, a variety of languages and vocal demands that test the best singers. The only change that I can see is that the chorus has grown from 80 members on stage to about 110. (Ms. Thom was noted for the rigor of her auditions and while the number who qualified each year was closer to 100, she would select about 80 for each concert.)

Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Opus 37, frequently referred to in English as his Vespers, is more properly called the All-Night Vigil (as in the Russian title Vsénoshchnoye bdéniye). Only six of the fifteen movements are from the vespers service. In this performance, we heard these six movements and five of the remaining nine: two psalms, the Magnificat, a hymn and the final chant. The score, often chant-like, at times subdivides the choir into more than eight parts.

The work, in the original Russian, was sung a capella except for an organ drone during the fourth movement (“Serene Light”) and the seventh (“Glory to God in the Highest”). I wondered if the drone was added in an attempt to prevent a loss of pitch. Even with the underlying drone, there were intonation problems in the second movement, the only point of significant error. The fifth movement (“Nunc Dimittus”) is known for its “Russian bass” part, which descends to the third Bb below middle C. A wise choice was made; the basses concluded the movement up an octave from the original score.

Noteworthy among the first six Vespers movements were the second movement (“Bless the Lord, O My Soul”) and the sixth (“Mary Full of Grace”). Very effective was the disciplined pause in the seventh movement before the final “Ghospodi, ustne moi olverzeshi…” declamation. (“O Lord, open Thou my lips…”) A wonderful change in color occurred in the eleventh movement (“Magnificat”), where the sopranos bounced on their notes in a rejoicing dance of angels. I wished that we still followed the nineteenth-century practice of demanding a literal encore, as I would have delighted in a second hearing of the entire Magnificat. The final movement (“Thanksgiving”) provided a calm and graceful conclusion.

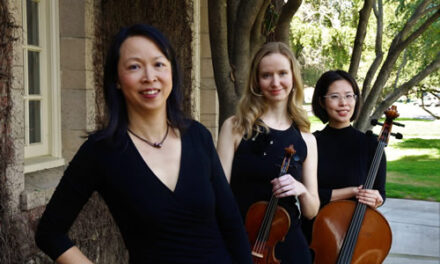

After a brief Christmas Carol Sing-Along to open the second half, Conrad Susa’s 1992 suite Carols and Lullabies: Christmas in the Southwest concluded the program. Three instruments – guitar, harp and marimba – provided an Hispanic-themed accompaniment. The ten movements are based on Spanish-language sources in dialects from the Castilian, Catalonian, Andalusian, Biscayan, Mexican and Puerto Rican traditions. Only one of these carols was familiar to me: in the Lutheran Hymnal you will find the Catalonian carol as “Cold December Flies Away.” At this time of year, we tend to hear the same old carols repeated endlessly; what a delight to be given totally new Christmas songs.