Even as the historically-informed performance movement has matured, countertenors remain vocal oddities. They’re basically our non-surgical answers to the castrati, the last of whom seems to have been Alessandro Moreschi, whose few recordings give pale hints of the grandeur of an artistic era that is gone forever. (Hear his recording of the Bach-Gounod “Ave Maria” here.)

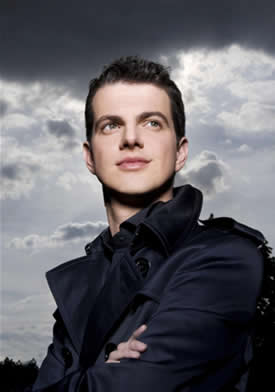

Starting with Alfred Deller, countertenors have gradually displaced the use of altos (or outright transpositions) in music composed for (altered) male sopranos or mezzo-sopranos. Among the great ones since Deller (who sang a recital at St. Mary’s in the ’50s) have been James Bowman, René Jacobs, and David Daniels (who was born in Spartanburg). To that short list one must now add Philippe Jaroussky, the brilliant young French artist who made his area debut in a concert presented by Duke Performances in Reynolds Industries Theater. Jaroussky is the real thing, the genuine article, a singer whose vocal qualities include the finest attributes of his best predecessors and virtually none of their shortcomings. Here’s a voice that is even, flexible, warm, of ample size, and with never a hint of falsetto in the traditional sense. Those “bucketsful of vocal diamonds” cited long ago in connection with the first countertenor who lived here (C. Michael Hawn) were constantly evident during Jaroussky’s program of seven arias – and three encores!

He sang with Apollo’s Fire, the baroque orchestra, based in Cleveland, that Jeannette Sorrell has made one of the finest in the world. The concert was the first joint appearance of the chamber orchestra with Jaroussky and the first date of a major tour. It was also one more example of the amazing, world-class programming being offered here in the Triangle!

The lineup consisted of music by Handel and Vivaldi, and the question posed to the audience in Sorrell’s program note was this: “Does Vivaldi deserve a place beside Handel on the baroque opera stage?” Based on what we heard, the answer is surely “yes,” but, truth to tell, we’ll require a good deal more staged performances of Vivaldi operas – to compare with the flood of Handel that has been part of that composer’s relatively recent renaissance – before we can know for sure.

That said, there’s much in common in the composers’ approaches to the formal ABA arias that were presented. These are basically two-sentence songs, the first line being given reasonably straightforwardly, the second, briefer sentence coming in contrasting tempo and mood, and the first then repeated, generally with extensive elaboration and ornamentation.

The arias given were from Handel’s Oreste (1734), Parnasso in Festa (a serenata or ode, usually listed with the oratorios, 1734), Imeneo (1740), and Ariodante (1735), and encores from Rinaldo (1711) and Serse (1738), from Vivaldi’s Catone in Utica (1737), Giustino (1724), and Tito Manlio (1720), and, as the first encore, from Nicola Porpora’s Polifemo (1735). Although three of the Handel works are reasonably well- known, the sources probably don’t matter very much, for (as Handel himself often demonstrated) the arias were often interchangeable.

The singing was from start to finish extraordinary – no other single word will suffice. Those who could get over a woman’s voice coming from the body of an exceptionally handsome young man – and the packed auditorium seemed to contain few who could not! – were rewarded with some of the very best countertenor singing yet heard.

And the fact that Apollo’s Fire was the backup band was just so much icing on the musical cake. In truth, the chamber orchestra – 14 artists, including its harpsichordist/director – would have been one of the season’s top attractions, even without the vocalist, so exceptionally fine is its ensemble and finesse. Here’s a HIP group that plays incisively, with wide-ranging dynamics, with a remarkable variety of tone color and nuance, and always in tune – and without stopping every few minutes to re-tune! Director Sorrell arranged several pieces for her group – an Allegro by Vivaldi that served as an overture and introduction for the singer’s first number, and a prelude for harpsichord by Handel that led directly into a Handel chaconne, the two serving as the “overture” to the concert’s second half. Along the way, two brilliant Vivaldi concerti demonstrated the high accomplishments of the band: the Concerto in G minor for Two Cellos (featuring René Schiffer and Stewart Pincombe) and a Sorrellization of “La Follia” (after the Sonata No. 12) for two violins (with Olivier Brault and Johanna Novom). There was virtuosity of the highest order in these works and in the accompaniments, too. This was all old music, but the performances brought everything to vivid life, as if the scores were being tried out for the very first time – and with the composers lurking in the wings (albeit probably on opposite sides of the stage…).

As noted, this was the first joint appearance of the singer and this orchestra, but even after the tour, it cannot be the last. Those who heard these artists at work were richly rewarded. Those who didn’t should be on the lookout for them, together or singly, downstream.

Till then, there are online performances by Jaroussky of the three encores (alas without Apollo’s Fire) – Porpora’s “Alto Giove,”and Handel’s “Venti turbini” and “Ombra mai fu” Enjoy!