It was a dark and stormy night. No, wait, that was last night, forcing a cancellation. The treacherous ice and snow had moved on out, and the North Carolina Symphony could combine two programs into one evening at Meymandi Concert Hall. And so this storied orchestra, along with a great crowd of enthusiasts, was able to put its Eightieth Anniversary Season back into gear in fine style.

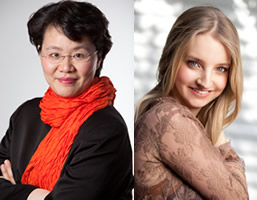

Reading background information on Mei-Ann Chen and all the orchestras that this young conductor has led, one might conclude that the North Carolina Symphony was the only one she hadn’t ever appeared with. Now that little gap in her résumé has been filled, and further, with astonishing verve and vibrancy.

This native of Taiwan first bounded onto the stage to lead the Overture from Rossini’s The Italian Girl in Algiers. Her uncommon athleticism became apparent as soon as the score (which she did not use) called for that startling change from meek piano to sudden fortissimo near the beginning of the piece. Her attitude throughout seemed to be, why limit yourself to standard arm waving. Let the whole body do the work. Here crouch, there lunge, never for theatrics but only for effective interpretations. The players certainly found no ambiguities in her directions. It became clear early on that all of her manifold accolades and awards indulged in no overstatements.

Yet another honored guest came on next, the (even younger) French pianist Lise de la Salle. The program notes declared that she “has emerged as one of the most acclaimed artists of her generation, praised for inspired performances of virtuosity and depth.” To judge by how adroitly she negotiated that Mozart Piano Concerto No. 9, K.271, she easily lived up to such high billing. Since this work featured no “opening tutti” for the players, she was able to take charge immediately. It was little short of sensational to note the light and mercurial qualities she brought to bear on that most challenging of piano material. Having been somewhat shortchanged in the opening bars, the players were able to shine in the dark and brooding Andantino movement. The closing Rondo furnished great entertainment of both sight and sound: In high-spirited give and take, the pianist would play a passage, then look over at the violins as if to say, “Your turn!”

This concerto is alternately titled “Jeunehomme,” referring to an enigmatic and evidently skilled Mlle. Jeunehomme who perhaps first played the piece for Mozart. What’s to prevent one from assuming that here is that mystery woman’s direct descendant?

Symphony No. 4, Op. 60 has long been considered the Rodney Dangerfield of Beethoven’s symphonies, sandwiched as it is in the listings between the towering Third and Fifth. It would seem that Mei-Ann Chen has resolved to correct this situation, showing that it deserves noteworthy respect. It is questionable whether anyone else has ever brought such “Eroica-like” grandeur to this four-movement work. Using her engaging animation and force of personality (again without use of printed score), she and the responsive players repeatedly elicited compelling sensations reminiscent of that composer’s universally acclaimed greatest works.

Anyone present for that post-intermission selection should henceforth have a new appreciation for the “Fourth,” and maybe even demand performances of it consistent with the one it received on a frosty Saturday evening in Raleigh on January 26, 2013.