In my last commentary on a Music for a Great Space organ program, I said that “listening to an organ recital online is limiting: the room’s acoustics are often barely evident; the sounds are limited to whatever reproduction one can extract from one’s computer.” For an organ recital, the acoustical environment is of great importance. As organ-builders often say, “the most important stop on an organ is the room it’s in.” But we do the best we can under the circumstances, with virtual concerts played for an audience most often listening from their homes.” For this concert, things sounded better as the performances were piped through my stereo system, rather than reduced to headphones.

In my last commentary on a Music for a Great Space organ program, I said that “listening to an organ recital online is limiting: the room’s acoustics are often barely evident; the sounds are limited to whatever reproduction one can extract from one’s computer.” For an organ recital, the acoustical environment is of great importance. As organ-builders often say, “the most important stop on an organ is the room it’s in.” But we do the best we can under the circumstances, with virtual concerts played for an audience most often listening from their homes.” For this concert, things sounded better as the performances were piped through my stereo system, rather than reduced to headphones.

Audio and video being pre-recorded rather than live-streamed, we were able to hear two artists performing on two organs at two different institutions: Marya Fancey played the Andover organ in UNCG‘s music building, while John Alexander played the Létourneau organ at Greensboro’s First Presbyterian Church. The artists’ biographical sketches may be found here.

It’s interesting to note that both Fancey and Alexander trace their organist’s lineage through Andrè Lash, who performed an earlier recital in MGS’s offerings this year. With such short programs (each playing two works totaling c. 30 minutes), it is difficult to form a complete impression of a performer. Fancey, who specializes in historical musicology, played a transcription of a brief vocal “Ave verum” by Caterina Assandra, an Italian nun who lived around the beginning of the 17th century. Fancey herself transcribed the work from its original tablature notation into modern notation, playing it with light flute sounds appropriate to its vocal nature. A gentle work, gently played. She ended her half of the concert with the four-movement organ Suite No. 1 by Florence Price. Here, Fancey was able to use the full resources of the organ. The opening “Fantasy” lived up to its title, being a wandering and essentially formless work. While very chromatic, I did not find it to be a 20th century re-creation of J.S. Bach’s famous Toccata and Fugue in D minor, as Marney suggested in her verbal program notes. The “Fughetta” brought the work’s most dramatic elements, while the episodic “Air” with its harmonically-inventive musical language, evoked some early organ works of Leo Sowerby, with whom Price studied in Chicago. The closing “Tocatto” (sic) evidenced Price’s African-American heritage in its jazz-evoking melodic sequences.

Fancey’s performance was well-registered and well-played, but lacked effervescence. If she can bring to her playing the verve which she displayed in some of her post-concert comments, it will make the music be more than just its pitches and rhythms.

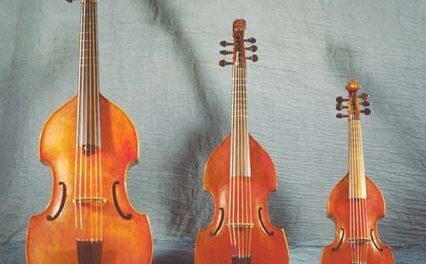

Alexander opened his program-half with the first movement (Allegro maestoso) of Edward Elgar’s Op. 28, the G Sonata for Organ. The Létourneau organ is, in reality, two organs: one two-manual mechanical (“tracker”) action in the rear gallery and the main Chancel organ, four manuals with electric slider chests which can also play the stops of the Gallery organ. This is a large instrument, with 123 ranks (sets) of pipes. It is large enough to be eclectic, with the appropriate sounds for playing Baroque, Romantic, or Contemporary music of all schools. Alexander showed off the English Romantic style sounds for which Elgar wrote: the full-throated Diapason choruses, augmented by the reed voices (trumpet/oboe/etc.) in the fortissimo sections. The microphone placement for such a large instrument isn’t easy; the bass lines didn’t come through with adequate volume in this recording, and some of the faster passage-work lost clarity in the room’s reverberation. While it would have been nice to hear the entire sonata, this single movement was a good choice because its multiple sections give ample opportunity for changes in sonority, showing off the instrument’s many-colored solo voices. The majestic sounds of the principal theme gave voice to the composer’s direction: maestoso. Alexander played with a dignified flair well-suited to this music.

The concert closed with a tour-de-force reading of the Te Deum (Opus 11) by Jeanne Demessieux, one of the most talented of all the great Parisian organist-composers. The reason we hear few performances of her music is likely because she wrote for her own prodigious technique. Like many of her organ works, the Te Deum requires a facile command of fingers and feet to essay its ferocious technical requirements. In a way, it is an extended, multi-themed toccata adorned with colorful and unexpected dissonances and rhythmic diversions. Alexander was equal to the challenge, bringing the concert to a vigorously-exciting ending.

Both artists, hosted by MGS’s Rebecca Willie, shared information about their careers and about organs and organ music in general, as well as answering questions submitted from the on-line audience.

We look forward to the coming 31st season of Music for a Great Space, in hopes that live performances will once again be the rule after this pandemic-altered year.

Those wishing to explore the YouTube world of compositions by Demessieux may enjoy this performance of her Te Deum by Renée Anne Louprette here.