The thirteen artists featured in Line, Touch, Trace live and work in North Carolina. That is all they have in common, yet their drawings make for a satisfyingly coherent and visually appealing exhibition. Curated by Edie Carpenter, Director of Curatorial and Artistic Programs at Greenhill in Greensboro, NC, in consultation with Jennifer Dasal, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Line, Touch, Trace is the first drawing exhibition presented in the museum’s North Carolina Gallery. The gallery is located just beyond the information desk at the entrance to the East Building.

In a curatorial statement beneath snazzy signage announcing the exhibition title, Carpenter introduces the hand-drawn line, the smudged touch of an artist’s fingers, and traced marks as visible expressions of imaginative thought. She expands on her succinct introduction to the exhibition in an interview published in the Fall, 2014, edition of the North Carolina Museum of Art’s Preview. There she notes that the immediacy of drawing gives the viewer privileged access to the creative process. Brief commentaries on each artist’s work are contained in wall texts unobtrusively interspersed throughout the exhibition. These reflections mercifully avoid didactic explanations in favor of thoughtful insights into relationships between medium and content. A combination of graphite, watercolor, and encaustic on panel viscerally conveys what Carpenter calls the “epidermal quality” of Tamie Beldue‘s Float (2013). In Hospice and Move, both from 2012, Kiki Farish adds a layer of textured pencil strokes over partially erased words and images to build up surfaces that evoke the “fluctuating nature of memory.”

Materials used in the thirty-two drawings on display are as diverse as the artists themselves, ranging from age-old traditional to up-to-the-minute contemporary. John Hill Jr.‘s droll fantasies are rendered in ink applied in dots and small squares to parody the four-color printing process of comic books; Matthew Micca‘s topographic abstractions are color fields stained with ballpoint pens (Fig. 1); and Lori Esposito‘s improbably symmetric plant forms hover on double-sided Mylar supports. With respect to style, the works represent an expansive concept of drawing that embraces Selena Beaudry‘s loose, gestural Color Pencil Tracing #2 (2013) as well as the exquisitely wrought detail of the serpents in Ippy Patterson‘s Escape from Eden (2003). In the many densely detailed drawings on display, obsessive repetition produces a wide variety of effects, among them the feathery, vibrant red fronds that couch the figures in Kreh Mellick‘s Three Girls (2013) and the delicate, lacy transparency of the scrim that hangs on the surface of Kenn Kotara‘s Making My Way (2011).

Some of the subjects are drawn from sources as familiar as the Bible, while others are inscrutably personal. Joyce’s Calendar (1995) is one of hundreds of works in which Viennese-born Fritz Janschka examines his own penchant for graphic inventions through the filter of James Joyce’s literary imagination. (I know this because I have been married to him for 38 years.) Jason Watson shows a predilection for popular American culture rather than highbrow Irish literature, assembling odd assortments of found objects into ensembles animated by strong tonal contrasts. Whether literary in inspiration or based on direct observation of visible reality, most of the drawings are original interpretations of venerable art-historical traditions. Patterson’s Escape from Eden unfolds in a hybridized format that reorients the Japanese handscroll and rethinks illustrated books in the western tradition. Mellick’s small drawings update the English Arts and Crafts approach to book illustration, whereas Kotara quite literally ramps up the size and scale of botanical illustrations. In his Category Two (2010) minuscule half-circles proliferate into aggregates of botanical motifs that at first glance resemble strings or spirals of algae seen under a microscope and on closer scrutiny the intricate floral designs in Japanese pattern books.

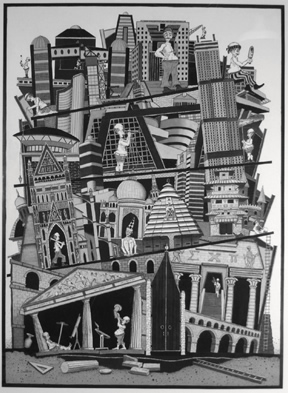

Other artists in the exhibition tap into a rich history of architectural drawings. Isaac Payne and John Gall are as different as Giovanni Battista Piranesi and M. C. Escher, two of their predecessors in this regard. Payne integrates recognizable figures in spaces that are at once illusionistic and abstract – an effect created by framing images of three-dimensional urban structures with collaged paper. Since Payne’s settings consciously reference museum architecture, it is entirely fitting that The Steps (2010) is hung to mirror the perspective of visitors descending the central staircase of the East Building, where the exhibition is mounted. In contrast to the disquieting disconnect between the figures and their monumental setting in Payne’s Billboard (2013), the quirky, pot-bellied figures in John Gall’sThe Babel Makers (2003, Fig. 2) are humorously displaced in a tower of architectural facades, neatly arranged in chronological order.

To their credit, Carpenter and the North Carolina Museum of Art designers made the most of the awkward, if prominent, space of the gallery designated since 2010 to work by North Carolina artists. They installed the exhibition in such a way that diagonal walls of different lengths are utilized to the artists’ advantage. Their groupings give space to the large works that need it and a more intimate viewing space to clusters of smaller works. In one instance Carpenter and her collaborators even capitalized on the proximity of a sculpture in the museum’s permanent collection, juxtaposing three of Beldue’s acrobatic silhouettes to the shadow cast by Bob Trotman‘s suspended Vertigo (2010).

The public opening was billed as a “meet the artists” event, and all were in attendance. Having traveled from across the state, they might well have expected a modest reception, but there was none. Line, Touch, Trace is on view until March 8, 2015, so for those who missed the opening, there is ample time to plan a visit. Greenhill is sponsoring a road trip on Saturday, October 4th, with talks by participating artists and a tour of the exhibition followed by lunch at Iris, the museum’s restaurant; for details see Greenhill’s website. Any additional programming will be posted on the North Carolina Museum of Art’s website.