The North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA) has landed two extraordinary exhibits, made more special because both are under the same roof, for one admission price, through January 17. In a rather small gallery is the Codex Leicester, Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) 500 year-old notebook containing scientific observations, mostly concerning hydrology and the movement of water. In the much larger multi-room Meymandi Exhibition Gallery, formerly where most of the NCMA’s permanent holdings of paintings were exhibited, prior to the opening of the new West Building, is the mesmerizing and possibly once-in-a-lifetime exhibit “The Worlds of M.C. Escher: Nature, Science and Imagination.” Among the many revelations and inspirations from both is the realization that da Vinci and Escher are not as far apart as you might think.

The first exhibit is officially called “Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Leicester and the Creative Mind,” and if there are words which can best describe it, I would say they are “reverence” and “awe”; that can be good and bad. On approaching the exhibit, a sharp left at the bottom of the stairs of the original NCMA building (now called the East Building), you are met by a security checkpoint that rivals onr of the TSA’s. I had hoped to be diligent and take detailed notes of what I would see, but even pens and pencils were taken away and placed in baggies for pick up after you exited. I can only imagine the insurance and security requirements that went along with procuring this historic collection!

The Codex Leicester may be the most important and famous of da Vinci’s many journals, written in his mysterious “mirror writing,” which means that it is actually a mirror image and thus must be reversed to be read — not that that would help us mortals understand any better. Saving his pennies from sales of hundreds of millions of copies of Microsoft Windows, in 1994 Bill Gates bought the Codex for $30,000,000, and this historic document is on loan directly from him.

The exhibit itself is in a single, darkened room, and it is set with display cases on two sides, each containing two pages from the Codex. Each side has a brief description of what the page is saying and a relatively simplistic explanation of the scientific principle. There are nine of these stations. Since most of the Codex is concerned with very specific and complex hypotheses on the movement of water, even the simplifications can be indecipherable. Except for a station where you can listen and see blown up translations of a page (for which there was a long line), that’s pretty much the exhibit.

Standing in front of these leaves from the Codex, most of what I did was just stare in awe at the actual physical object that perhaps the greatest mind in human history actually wrote. However, as an exhibit, overall, I felt it lacked an accompanying learning component that would have made it much more enlightening and enjoyable. I’m not proposing dumbing down anything, but perhaps an adjoining room where models and displays could have helped illustrate da Vinci’s principles for those of us who are not geologists or engineers.

***

Maurits Cornelis (M.C.) Escher (1898-1972) was a Dutch graphic artist whose drawings and designs incorporated aspects of mathematics and science in such a revolutionary way that he had little precedence and no real successor. Although he generally downplayed his training and knowledge of the scientific realm, his astounding and bewildering creations reveal a perception of the world framed with an uncanny ability simultaneously to present what both is and what can never be — or can it? A lovely phrase used to describe these works is “impossible realities.”

The NCMA is presenting the most comprehensive Escher exhibition ever assembled in the United States. It is a visual feast in numerous media, some of which I had never heard of: drawings, woodcuts, woodblocks, lithographs, lithographic stones, watercolors, mezzotints, and even a few sculptures. There are more than 130 items in one eye-popping, mind-bending experience after another. As if this weren’t enough, the exhibit’s flow and arrangement is a masterpiece in itself. Each room is perfectly lit and large enough to hold the anticipated throngs of Escher fans. There is a general theme to each room or wall of works. There are annotations beside each work, large and clear enough to read from a distance, and often containing Escher’s own comments on each item. The NCMA has also generously dispersed throughout the rooms for your perusal numerous copies of their self-published book of the exhibition, The Worlds of M.C. Escher: Nature, Science and Imagination. You might also want to splurge and buy this book at the gift shop. (There is no photography of any kind allowed in the entire exhibit.)

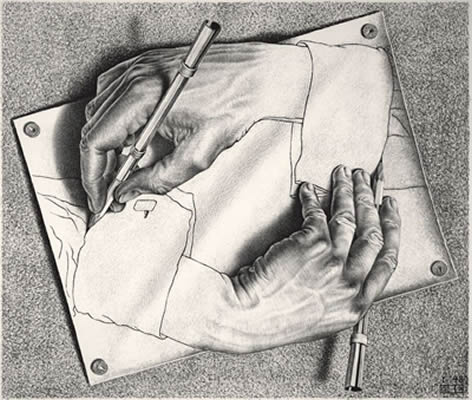

Many of us of a certain age recall the “discovery” of Escher’s works as we tried — perhaps with a boost of some external sensory enhancements — to decipher some of his iconic drawings, such as Bond of Union, Drawing Hands, and Relativity. These and more of his “impossible reality” works, including some of the most iconic of the 20th century, are on hand for some friendly brain teasing.

The exhibit is, for the most part, arranged chronologically. From his beginnings as a landscape artist in Italy to his illustrations of bugs and insects to some spectacular late-in-life works that I had never before seen, it is all here for in a truly once-in-a-lifetime artistic opportunity. Nearly two months remain to see this exhibition, but do not delay — and arrive early to avoid having to battle the expected record-setting crowds. See the sidebar for details.