Heroes. The word’s so overused nowadays that it’s almost meaningless. But in the arts, there are heroes – sung and unsung – whose work affects others, often for whole lifetimes, and if we can call innocent victims of various tragedies – people who have had the misfortune of being in the wrong places at the wrong times – or those who merely did their jobs – heroes, then surely we can use the noun to refer to creative and performing artists, too…. There are scads of these folks, around the country – teachers in studios and classrooms, violinists in community orchestras, folks who tithe for the arts or who serve on boards and committees of non-profit groups, people who write poetry or plays or music for their own pleasure, often without any viable hope of public performances. There are band directors and stick-wavers of all stripes – those who lead choirs and chamber orchestras and various other local and regional ensembles. Some of these people achieve a measure of fame – or notoriety – in the areas where they work. And it’s often extra-musical stuff – luck, politics, patronage, even – that propels some of ’em to nationwide or international levels. Ideally, the determinant centers on artistic merit, but that’s not invariably the case.

To narrow the field, think of stellar teachers – teachers who can do and teach, too. Most of us have had such teachers, and some of them have influenced us far beyond the classroom. In Raleigh on November 3 and 4, tribute was paid to one such teacher by another – J. Mark Scearce, a teacher and composer who now heads NCSU’s Department of Music, spoke of a guy who glanced at his first score, years ago, at Indiana, and who immediately suggested a change that made it better – and pinpointed the work’s most problematic section as well. The teacher was – and is – John Eaton (b.1935), composer extraordinaire. He’s a certified genius – the recipient of one of those MacArthur “genius” grants which, in his case, gave him the wherewithal to pursue his artistic dreams. You can read about him in books, and if you do, you’ll learn that he’s been doing music for a long time – he got 2-1/2 pages in David Ewen’s classic American Composers: A Biographical Dictionary, and it was published 23 years ago! In the Price Music Center and at the College of Management, Eaton gave a series of fascinating lectures, sponsored by the Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholar Program and hosted by the local chapter of Phi Beta Kappa and Richard L. (Larry) Blanton, Director of the University’s Honors Program, in which he introduced his music – chamber works he calls “pocket operas,” larger stage works, and chamber music – to small groups of perhaps skeptical people who were, one suspects, thoroughly convinced and thus devoid of skepticism when he was through. Eaton is special, and some would say he’s unique, but I hasten to repeat that there are many Eatons abroad in the land. My “Eaton” in the fields of poetry and Shakespeare was the late Clifford Lyons, and my “Eatons,” in terms of listening to “new” music, were (and remain) philosopher James Lawrence Cole and composer Roger Hannay, people who did for me what Eaton did, perhaps more tangibly, for Scearce. We’d be the first to admit that it was the influence of these teachers and mentors that made the difference, that we’re not talking imitation here. It’s a fact that Scearce’s music bears little superficial relationship to Eaton’s, and indeed that Eaton’s music is nothing like the music of his own teachers – Babbitt, Cone, Kim, and Sessions….

Eaton – a hero to some, but basically unsung to others, including scads of opera people and music lovers in general – has the advantage of having produced works that can be sung, since so much of his work is operatic in nature. His career has involved long tenures at Indiana and the University of Chicago and in Rome, and his c.v. is studded with the kind of ticket-punches that many scholars can only dream about, but two things – his teaching and his creative output – will be his lasting legacies, and it was his music that was the main focus of the talks he gave, all of which were illustrated with excerpts from his compositions.

When I read the advance PR about Eaton, I was put off by the hype that he’s “The most interesting opera composer writing in America today” – until I discovered that the author of that blurb was Andrew Porter. Eaton’s works are unlike any other music I’ve ever heard – a bold, blanket statement, to be sure but, based on what was sampled, it’s absolutely true. The theme of the visit was “On Different Tracks: The Simultaneous Presentation of Different Levels of Reality in Opera.” That’s fair enough, and he’s certainly not alone in viewing the genre as existing in various planes all at once. His subjects are familiar enough; anyone conversant with baroque or contemporary opera – ranging from Richard Strauss to Gottfried von Einem – will recognize some of the universal themes he’s addressed. His influences include jazz – he played some recordings of “free” (some would say “very free”) jazz versions of spirituals that pressed the improvisational envelope well beyond the norm – and (for want of a better term) various “world musics.” He explained that his own music involves electronics – he worked with the late Robert Moog and others – and quarter and microtones, his interest in which stemmed from his involvement in jazz, wherein everyone but he and other pianists play all those notes between the notes of a conventionally-tuned keyboard. If you think about it, microtonality is a completely natural thing for most of the world – aside from folks locked into the “equal” or well-tempered legacy typical of what we call Western Art Music that started, nominally, with JS Bach’s Mighty Forty-Eight. Now, we’re so tied to equal temperament (which is anything but…) that it takes a radical pioneering type – Ives or Cowell or Partch or Cage – to remind us that ’tain’t necessarily so. Gurus of electronic music have escape routes, but Eaton wasn’t content with analog or digitally-generated computer music, for it lacked (and lacks) a human touch. So his work with Moog led to machines that players can control, just as live musicians have since time immemorial injected themselves into their realizations, whether from the printed page or as passed down in the oral tradition.

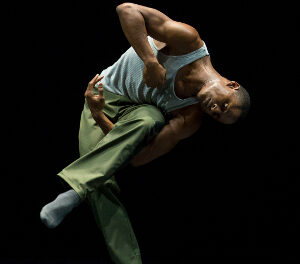

He doesn’t mess around. Eaton’s “pocket operas” involve small instrumental ensembles whose members are expected to wear costumes, act, do things you’d never expect a self-respecting wind or brass player from a symphony orchestra to do in public (like the clarinetist who turned somersaults while playing), and so on. The point is not, however, difference for difference’s sake. The point is to serve the drama and, based on the examples we saw, Eaton pulls it off as well as ol’ Richard did in his operas that espoused the principle of “Gesamtkunstwerk.”

Readers can – should – look up his works at several sites: http://www.schirmer.com/composers/eaton_bio.html [inactive 9/06] http://composers21.com/compdocs/eatonj.htm, and http://www.amc.net/member/john_eaton/works.html [inactive 8/07]. In Raleigh, on the afternoon he arrived, we heard bits and pieces from many of his stage works, including pocket operas Peer Gynt, Let’s Get This Show on the Road, Don Quixote, Golk, Pinocchio, and …inasmuch. These are short and are often paired, and it would be wonderful to have some enterprising outfit put them on – or bring productions of them – here. It’s apparent that the music is incredibly difficult, but it doesn’t sound hard – it really does come across as total theatre, and it draws in the audiences, even when seen via second- or third-generation video tapes. It’s not exactly crossover music, although there are elements of jazz here and there. The best way I can describe it is to say that it’s new and fresh. Those who admire Kurt Weill, Bernstein’s theatrical music, the skill with which Strauss set vocal lines for women singers, and classic cabaret songs will find that Eaton’s music strikes responsive chords – and more.

The evening of November 3 brought a presentation on Eaton’s major stage works – fantastic pieces that have been produced by major companies, including the San Francisco Opera, the Santa Fe Opera, and Lyric Opera of Chicago. These included The Cry of Clytaemnestra, Danton and Robespierre, Myshkin, and The Tempest (adapted from Shakespeare by the aforementioned Andrew Porter), which capped a remarkable evening so effectively that one might have rushed out into the street (well, on second thought, maybe not Hillsborough Street…) to tell the world about it. Eaton cautioned that the tapes didn’t do these things justice, and that’s surely true. One suspects that recordings of his music don’t do it justice either. For sure, our appetite for sampling the Real McCoy was whetted.

The final presentation, given on the afternoon of November 4, involved chamber and choral music. It began with the only live performance of the visit – Eaton played his earliest microtonal work, a Fantasy (1965) for “Two Pianos Tuned a Quarter of a Tone Apart (Played by One Pianist).”. The setup involved NCSU’s new grands, angled so Eaton could reach both keyboards. Like violist Jonathan Bagg’s recent performance of the quarter-tone first number of Ligeti’s Sonate, this took some getting-used-to, but ultimately it made its points well enough that one would welcome the opportunity to hear it again. As it happens, the Fantasy has been recorded (American Decca DL-710154); chances are the performance was better than the record (because, as we’ve said from time, live performances are invariably superior to canned ones). There was a sample of a (recorded) live performance done on a synthesizer, some jazz bits from Eaton’s “other” life, and a tape of a conventional Mass (conventional in terms of text) that was one of the most unusual things heard during the visit. Post-presentation discussions helped nail down some of the gaping questions, including one concerning the reception of his music. It is a matter of record that the Eaton operas given by major companies have wound up being completely sold out by the ends of their runs, with ticket scalpers doing their dastardly things in some locations, as a result. Eaton’s that good – that “hot.” We gotta get him back down here, post haste, to shake up our staid establishment – and perhaps to revitalize our entrenched opera companies, too!

Note: Limited discographies are included in the first two urls provided, above.