There was a bittersweet quality to the last concert of the Foothills Chamber Music Festival in the great room of Reynolda House August 21. Co-founder/director Rachel Matthews announced that this was the last concert that they would play in the grand salon-like room that evokes the experience of attending artistic soirées of yesteryear. Performances next season will take place in the auditorium of the new addition to the museum house. This should alleviate the pressure that this year’s fire code seating restrictions have caused.

The web of connecting relationships among all the composers on an unusually inventive program was complex. French singer and composer Pauline Viardot (neé García) was admired by Brahms (she premiered his Alto Rhapsody) and encouraged and supported Fauré, who in turn became a mentor to many musicians including Ravel, Enesco, and Nadia Boulanger. At that time, Boulanger seems to have mentored every American composer in Paris except Howard Hanson! Among her students was the major African-American composer Adolphus Cunningham Hailstork, who also studied with Vittorio Giannini at the Manhattan School of Music. Giannini became the first president of the NCSA, fitting the festival’s theme this season, “All Roads Lead to Winston-Salem!”

Pianist Matthews proved to be an exemplary Brahms interpreter, bringing plenty of fire and rich sonority to the composer’s sweeping first intermezzo from Six Pieces , Op. 118. Ideal pacing and phasing combined with crisp articulation brought out a sense of passing or loss in the second intermezzo. The pair served as a fine adieu to the great room.

Soprano Jennifer Zetlan was joined by pianist David Shimoni for some truly choice selections from the French art song repertory. Dating from his protégé years in the salons, Fauré’s small song cycle, Poème d’un jour , Op. 21 encapsulates three stages of love – “Recontre,” “Tourours,” and “Adieu” – giving three canvasses that the singer can take in different ways. According to Émile Vuillermoz, in Gabriel Fauré , “fill(ing) the songs… with great sincerity of emotion” is a recent interpretive approach. Zetlan used the traditional approach, seeking the “slightly ironic” – which better fits the sense of the poetry and the composer’s character, too.

It is rare to even hear a recording of anything by Nadia Boulanger, much less to encounter her songs in live performance. While in her early 20s, she became a protégée of the distinguished pianist Raoul Pugno, and in 1909 the pair collaborated on a large song cycle entitled Les heures claires . From this cycle, “Le ciel en nuit s’est déplié” (“The night sky unfolds itself”), was sung. Zetlan and Shimoni captured the essence of lovers basking in night’s embrace. More immediately striking was “Soir d’hiver”(1914-15), which deals with a war widow, watching over her child in a crib. Throughout the songs, Zetlan sang with exemplary diction and a fine, even voice, displaying excellent intonation and firm high notes. With the piano lid fully raised, Shimoni balanced ideally and accompanied with refined senses of style and color.

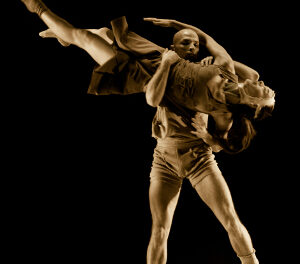

What happened next might have been appropriate for, say, a recital of Gershwin show tunes or operettas but exceeded the bounds of good taste for a recital of Mélodies. The last song performed was “Aime-moi,” a text by Louis Pomey arranged for voice by Pauline Viardot and set to the music of an Op. 33 mazurka by Chopin. Shimoni arose from the piano and presented Zetlan with a card, asking her to read it. The song was presented as a mini-drama. Reading the card as she sang, the soprano joined the pianist on the bench, hands wandered, and a clinch was narrowly avoided. By the end of the song, Zetlan had scissored a heart from the card and given it to the pianist. This was pretty much a dramatization of the text.

Adolphus Hailstork completed his String Quartet No. 1, part of a set of new works dedicated to the Virginia Chamber Players, in March 2002. An online program note by Jennifer Snyder and Rebecca Gilmore Shoup, written for the Ambrosia String Quartet, quotes the composer’s statement that “All of the material of the work was derived from the melody of the second movement.” All four movements seem dominated by a driving rhythm that interrupts even the mellow trio of the third movement. The work was played with great commitment and energy by violinists Amy Appold and John Fadial, violist Amadi Hummings, and cellist Elizabeth Vanderborgh.

Matthews’ program notes quote Virgil Thomson, writing about Vittorio Giannini: “…he writes like a master… with such fine skill and such pretty taste that no one can deny him a place among the authentic composers of our time.” The more of his music I hear, the more impressed I become. With rich scoring and inventive melodies, his three-movement Piano Quintet was an apt anchor for a program that began with Brahms. The first movement, an allegro con spirito with a passionate sweep, is opened by the viola, soon joined by the piano and then the others. The cello begins the adagio with a sad, wistful melody; the movement then features delicate writing for all five instruments. An episode for piano and muted strings is but one feature of the concluding allegro. Shimoni played with passionate commitment while never covering his string colleagues. Appold and Fadial played with closely matched intonation and phrasing while Hummings and Vanderborgh brought extra luster to the lower range. The give-and-take among the five players was a delight to watch and to hear.