The Fifty-first season of the Eastern Music Festival opened this week on the campus of Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina. A stellar performance by the Festival Orchestra under the direction of Gerard Schwarz opened the Saturday night series (the faculty orchestra plays Saturday nights and the two student orchestras play on Thursday and Friday nights, respectively).

Each Saturday concert this season will open with an American work, most composed to honor the final season (2010-11) of Maestro Schwart as Music Director of the Seattle Symphony. This concert opened with two lush movements written for piano in 1893 by Johannes Brahms, Sechs Klavierstücke (Six Piano Pieces), Op. 118, Nos. 1 and 2, transcribed for orchestra by the Chinese-born American composer, Bright Sheng. Perhaps one should say “recomposed” for orchestra rather than transcribed, because Sheng made them sound like long lost movements from an undiscovered symphony by Brahms himself. These are gorgeous pieces, the first passionate and the second tender. It was a pleasure watching the orchestra dig into these pieces, especially Concertmaster Jeffrey Multer, who leads by example, miming the musical events as they happen, especially the changes of dynamics.

The two movements were orchestrated by Sheng at different times, and in reverse order. He had orchestrated the well-known and popular second of the Six Pieces by Brahms several years earlier, naming it, for some undisclosed reason, “Black Swan.” The first movement, named “Prelude to Black Swan” was orchestrated and premiered during Schwarz’s last season in Seattle. I would like to see Sheng orchestrate a couple more of the Stücke (or one of the 18 other movements in the adjacent Opp. 116-119) and present the work as a de facto symphony although the key relationships might prove a challenge. At the very least these “Black Swan” orchestrations should find their place in the repertory although the high rental fees charged by publishers may inhibit this.

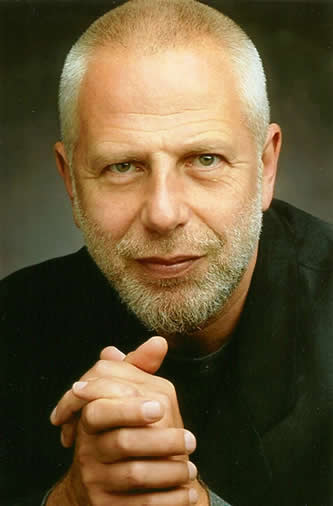

After a lengthy pause while the student interns practiced resetting the stage for the piano concerto, we welcomed the iconic Russian-American pianist Vladimir Feltsman in the Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37. More symphonic in nature than most classical concertos, this middle concerto of Beethoven’s five for the piano begins with a lengthy orchestral exposition which the orchestra and Maestro Schwarz played magnificently. Finally bursting in with scales in octaves, the piano took over and dominated the concerto from then on.

Feltsman plays with a clean precision and a remarkable clarity in all registers. The mannerisms which used to irritate musicians and audiences alike (I once saw him conduct the tympani solo at the end of the Emperor Concerto) have calmed down to some innocuous wavy gestures of the left hand. The cadenza was magnificent, especially the martial Presto and the gentle yielding trills which end it.

The shock of E major (after so much C minor) as the second movement opened, with just the piano, was palpable and the sextuplet section in G major with the dialogue between bassoon and flute over liquid arpeggios in the piano was gorgeous. The hushed tone of the muted strings contributed to the extraordinary contrast between first and second movements.

The third movement interrupts the bucolic mood with crisp rhythmic reality, punctuated by quasi cadenzas of arpeggios and trills. A new theme in A-flat major introduced by the clarinet gets serious play by both orchestra and soloist before giving way abruptly to a fugato based on the first theme of the movement. The fugato peaks in a series of repeated eight notes (Gs then A-flats) only to modulate enharmonically to E major (our “shocker” from the second movement). A last cadenza leads to the final surprise, a Presto coda in 6/8 meter and in C major! The audience gave Feltsman a well-earned standing ovation, but the soloist, gesticulating about the heat, did not reward the audience with the hoped-for encore.

The second half of the concert was dedicated to a performance of the popular Symphony No. 3 in C minor, Op. 78, “With Organ” by Camille Saint-Saëns. Officially divided into two movements, the symphony nonetheless follows the traditional 4-movement schema but uses the Lisztian cyclical style which causes the thematic material to evolve throughout the whole piece. Fittingly, the symphony is dedicated to Franz Liszt, who died shortly after the symphony’s London premiere in 1886. The orchestra swelled ranks, adding a piano (four hands) and various and sundry low instruments (English horn, bass clarinet, contra-bassoon, tuba) and an organ. Purists argue for performing the work only in halls with outstanding pipe organs, but Dana Auditorium has no organ. So the back wall behind the percussion was lined with nearly a dozen speakers, necessary, no doubt, for producing some of the very low notes in the organ part.

There was some remarkable fast tonguing in the winds in the first movement. The effect of the piano arpeggios in the last movement is scintillating and the hushed tones of the organ in the slow second section gave it a spiritual quality. But the real reason for the symphony’s popularity lies in the grandiose loud passages, especially near the end when the organ “pulls out all the stops.” Naturally, the bombast elicited another standing ovation!

This year the Eastern Music Festival has engaged Bernard Jacobson, a music critic and author from the Puget Sound area, to write the program notes in the playbill (temporarily missing) for the Festival. While they are informative they are neither as enlightening nor as entertaining as those of recent years, written by Greensboro resident, author and critic, William Trotter.