The latest concert by Duke’s renowned Ciompi Quartet, presented by Duke Performances in Baldwin Auditorium on one of the very busiest weekends of the season, culturally speaking, featured the Lark Quartet (est. 1985) and the Durham-based host ensemble (est. 1965) in a bracing program of mostly unknown music by the great Dane Niels Wilhelm Gade (1817-90), Turkish composer Füsun Köksal (b.1973), and New Orleans native Andrew Waggoner (b.1960), currently teaching at Duke. The latter is coincidentally the spouse of the Ciompi’s cellist, Caroline Stinson – who is also the Lark’s incumbent cellist – which accounts for the presence of yet another guest, cellist Laura Sewell, who’s no longer a member of the Lark but who was its founding cellist, and who was summoned to round out the Lark foursome.

The Lark is ending its 35-year run as a professional quartet this season, so there’s much to celebrate – and more than a little cause for nostalgia among those who had savored their often-radiant performances across that long span (including pre-CVNC performances in North Carolina).

The appearance of the two ensembles +1 on the same stage was cause for even more celebration.

Gade is a name that survives on the fringes, despite a copious work list. His symphonies hold some sway in comparison with Carl Neilsen’s, who came later (1865) and lived into the 20th century. Gade’s Octet for Strings clearly displays Mendelssohn’s influence if not his teacher and mentor’s brilliance. Hearing it was a treat, since it’s so rarely played, and the performance was likewise a delight, for there appeared before us eight fabulous artists whose relish at this opportunity to perform together, with Stinson as the pivot, as it were, was palpable throughout.

Stinson introduced the Turkish work, which was played by the CQ alone. Composer Köksal is female, Muslim, and (one might say) brave to have ventured into the string quartet idiom, considered the holiest of holies in Western art music. There are surprisingly few echoes of the Middle East, absent a good bit of falling away, pitch-wise, and some passages of extreme sadness. (One section is actually marked “dolentemente.”) Offsetting these, there’s considerable intensity and drama as the music unfolds, and indeed it was possible to hear the stirring of the mix that Stinson had foretold, as textures and figurations that began in the background, in some instances just barely audibly, came gradually but inexorably forward. Getting there is clearly part of the process, and the audience seemed engaged throughout – although the milestones listed in the program (the four tempo and mood indications) didn’t provide a whole lot of help to some of the listeners.

Part two was given over to a substantial introduction to Waggoner’s not-insubstantial “Ce Morceau de Tissu for 2 String Quartets” – and note the specific designation does not include the word “octet.” It was commissioned as part of the Lark’s leave-taking. I’m not sure that there was quite enough explanation, so there’s regret that a Nov. 22 intro to the piece at Duke was not more widely publicized.

That said, it’s available on a celebratory Bridge CD comprising four compositions commissioned by the Lark as part of its grand farewell, played thereon by the current Lark and the original Lark (which adds up to eight…).**

The music runs in parallel, we were told, as the two ensembles (with Stinson rejoining the Lark, and Sewell playing with the Ciompis) begin somewhat out of synch but – after an extended period of time – gradually reach some semblance of consonance. Ce Morceau de Tissu was inspired by the work of Fatima (or Fatema) Mernissi, a founder of Moroccan feminism – another brave thing to have done – and specifically on Le harem politique. Wagonner spoke of his fascination with this person and her work and the increasing relevance of both. (When this writer was in Morocco, feminism was strictly closeted, if it existed at all….). And that makes the score relevant to the Lark, a pioneer in the chamber music world that forged its own special path and commissioned many pieces by women.

Waggoner’s piece is a set of variations that exist as a continuously-played work lasting about 15 minutes, loaded with energy and incisive playing (as realized on this occasion), and laced with more than a few glorious solo bits and a whole lot of squaring-off of cello v. cello, viola v. viola, and the like (which, absent the foot stomping, brought vividly to mind Old Giorgio Ciompi himself, squaring off with former violist George Taylor in CQ days of yore). One also thought of massive tectonic plates scurrying around (slowly of course) beneath our feet, deep in the crust – yes, it was at times that powerful and that powerfully evocative. At the end there was a hint of lyricism – enough to prompt the hope that a local rehearing will be possible at some point. When that occurs, here’s a vote for more markers to aid listeners who don’t have the score before them as the work unfolded. But make note of that CD, which provides immediate gratification for those who seek it.

Area composers had turned out in force, and it was they who led the vociferous and enthusiastic reception accorded to Ce Morceau de Tissu when it concluded.

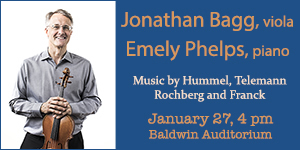

*The other artists were Eric Pritchard and Hsiao-Mei Ku, violins, and Jonathan Bagg, viola, of the CQ; and Deborah Buck and Basia Danilow, violins, and Kathryn Lockwood, viola, of the Lark.

**The other Lark commissions contained on the CD are John Harbison’s Quartet No. 6, Kenji Bunch’s “Megalopolis,” and Anna Weesner’s The Eight Lost Songs of Orlando Underground.

PS Waggoner’s music has figured prominently in CQ programs since Stinson’s appointment. Here are links to three previous reviews: June 25, 2018, September 29, 2018, and June 18, 2019.