The Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, led since Zane’s death in 1988 by his partner Bill T. Jones, has long been an American Dance Festival favorite. Jones is a rare creature: a preternaturally powerful dancer who has become one of the greatest, most intellectual choreographers of our time, while maintaining his own splendidly open and direct kineticism through his 10-member company. Jones’ rigorous mind ranges over many topics, and he crafts his dances to suit them, so one never knows quite what a program will offer, except that it will include stunning dancing — chests open, arms out, heads up — carried out by beautiful, thinking, feeling human bodies.

In the ADF’s first regular Durham Performing Arts Center performances this season, the finale is the glorious, wrenching D-Man in the Waters, first choreographed by Jones in 1989, not long after the death of his partner, Arnie Zane, with whom he had developed a dance language flexible and clear enough to explore identity issues and make social commentary without sacrificing any of the prerogatives of dance. This ADF-sponsored reconstruction is based on the 1998 revision of the work. It is set to Felix Mendelssohn’s Octet for Strings in E-flat major, Op. 20, well played by members of the Durham Symphony Orchestra.

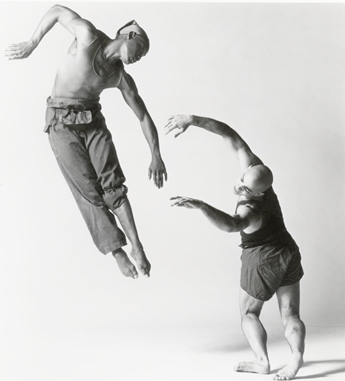

D-Man takes place in a world in which the normal medium for breathing and moving has become watery. The dancers are buoyed by it; submerged and buffeted; frustrated, cleansed and freed. The invisible waters separate them, and bring them together. They dive under; they breach the surface. They become the water — the tide at the moment when it turns, going both in and out from the shore, the waves tugging at each other from with opposing forces. All the lifting, carrying, rescuing actions become a poignant reversal of the old litany: In the midst of life, we are in death. Yet death the all-powerful destroyer is mocked again and again by the surging life of dancing bodies. Death will take all the bodies, but new ones will take their places — as in this reconstruction — and Death can never take the Dance.

Two wonderful pieces precede the intermission. The evening opens with Spent Days Out Yonder (2000), to the andante from Mozart’s String Quartet No. 23 in F Major, K 590, also played live by four members of the DSO. The sprightly music brings out lovely rippling movements, and the foursquare arrangement of the dancers emphasizes its uncompromising structure. Bill T. Jones makes great use of his dancers’ backs, which tend to be remarkably wonderful to look at, and in the first part of this dance, we are treated to a trio of them. The dancers don’t look our way — they are looking out yonder — they separate us from their vision just as much as they conjure it for us.

The program’s middle work, Continuous Replay, would be the show-stopper for your average dance troupe, but here is a hot warm-up for our cool plunge into the waters that will follow. Originally choreographed by Arnie Zane in 1977, the work was revised by Bill T. Jones in 1991, and includes a haunting, delicate soundscape by John Oswald that seems critical to the richness of the conception. A fair number of dancers take their clothes off on stage, but few stride naked onto the stage and later add garments. Led by Erick Montes as “the clock,” the dancers gradually form a line across the stage. They stand sideways to the proscenium, so that we may see their profiles in Robert Wierzel’s canny lighting, and periodically turn their heads to look at us. As they build a series of bird-like movements and gestures, still in the line, they begin to glisten with sweat, and the light picks up that gloss, while it sculpts the shadows. Especially in the large steps and lunges with the downstage legs, the dancers look like they were lifted from ancient Greek vase paintings, in which men and birds combine identities. Once they break free of the line, change and interchange take over, in a rather comic perversion of Escher-like patterning. Into the glorious nudity comes a man in black socks. Here comes a woman in a snug leotard. After a number of tight black garments appear, flowing white ones begin to take their places. The cyclic feel of this work is so strong that you may imagine it repeating, again and again, just out of your line of vision, long after it has played out on stage.

This highly recommended program continues June 17-18. See sidebar for details. Also recommended is a new film about Jones and his creative process. A Good Man premiered at the Full Frame Festival in Durham this spring; ADF is featuring it during its International Screen Dance Festival on June 26, after which it will run on PBS in the fall. Taken together, this concert and the film offer an unusual opportunity to delve into a great living artist’s oeuvre — past, present and future possible.