This Saturday concert found the Charlotte Symphony’s Music Director Christof Perick giving his all in his role as an advocate for the composer. Arnold Schoenberg’s revised 1943 full-orchestra string transcription of his 1917 string sextet, Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), opened the program. While this work is largely tonal, Schoenberg’s creation of serialism was taken up by academic composers whose iron domination of much of the music of 2oth Century has been resoundingly rejected by audiences. This broad revulsion unfairly tars some fine music. Modern music has become the kiss of death for the box office. Part of a music director’s duty is to foster an audience’s openness to music he feels strongly about.

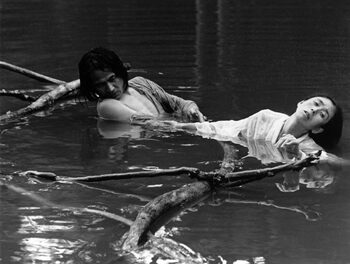

Schoenberg’s name unjustly spooks the average concertgoer. This was the Charlotte premiere of the composer’s transcription of Transfigured Night for full orchestra. Before playing the work, Perick addressed the full house in Belk Theater at length. After placing Schoenberg into the context of recent music, he led his musicians in some dozen important excerpts, including the one atonal portion. The program book reprinted Verklärte Nacht, the poem, by Richard Dehmel, who bridged the sensuality of Impressionism with the intense spirituality of the new Expressionist movement in literature. The poem conveys the conversation and mood between two lovers walking in the moonlight. The woman is pregnant from a previous casual encounter and reveals this to her newly-found true love. Schoenberg’s music conveys the shifting emotional mood and atmosphere of the scene.

I generally prefer the clarity of Schoenberg’s original string sextet version, but Perick made the strongest possible case for the transcription. Each string section played with perfect unity, making each musical strand crystal-clear. Perick constantly refined dynamics and phrasing to great effect. Concertmaster Calin Ovidiu Lupano and principals Alan Black, cello, and Alice Merrill Kavadlo, viola, gave strongly characterized solos. The conductor had a firm grasp of the over-all ebb-and-flow of the work, and he molded it superbly.

This was the first time I have heard the orchestra since Perick has modified its seating. He has retained the divided violins, with the firsts on his left and the seconds on his right. The placing of the cellos behind the first violins while moving the violas over behind the second violins was new. This did not affect the Schoenberg much but came into play in the Beethoven selection when the double-basses were concentrated behind the cellos.

The so-called “original instrument” movement and a more widespread respect for Beethoven’s metronome markings have led to faster performances that eschew old-fashioned Romantic expressive dawdling on the part of a conductor’s whim. Perick’s reading of Beethoven’s delightful Symphony No. 6 in F, Op. 68 (“Pastoral”), was sunny and lively. The brisk pace of the opening movement was a fast walk if not an outright jog into the countryside, much as a cardiologist might have prescribed. The Scene by the Brook was filled with a myriad of exquisite details: violin trills, gurgling woodwinds, and the famous quote of the call of the cuckoo. The rustic quality of the third movement was fully brought out with careful attention to rhythms. The brass and percussion had a field day, conjuring up the thunderstorm in the fourth movement. Everything came together well in the last movement, the composer’s pantheistic hymn to Nature. All sections of the orchestra played well and there were too many fine solos to begin to name them all. The horn section had a great night and the close juxtaposition of the double-basses behind the cellos helped make the small number (six) of the latter less of a liability.