It was heartening to see the Carolina Theatre filled with an enthusiastic audience for the Chamber Orchestra of the Triangle‘s enterprising program of music by accessible and popular composers. Artistic Director Lorenzo Muti had selected works scaled perfectly for performance by a chamber orchestra, as well as two having different local connections.

Symphony No. 96 in D by Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) has always been nicknamed the “Miracle” because the crowd at a performance rushed forward to see the composer take his place at the harpsichord thereby missing the fall of a huge chandelier. Recent research has proved the London performance was of the 102 Symphony instead. Like all but one of the composer’s “Twelve London Symphonies,” No. 96 opens with a short, slow introduction ending with a plaintive oboe solo leading to a playful allegro, toying with expected tonality among other tricks. Londoners loved the lightly scored, rococo andante with its sudden harmonic and thematic shifts. Haydn delights in imaginative solos for the woodwinds and winds. The vigorous minuet features a central trio evocative of an Austrian peasant Ländler. The finale is regarded as one of the composer’s wittiest with what Edward Downes, in The New York Philharmonic Guide to the Symphony, calls “a cunningly constructed ‘teasing’ rondo.” Muti led a marvelous performance with an ideal choice of tempos, fine balance between sections, and a strong sense of style.

Section discipline and precise ensemble were married to the joy of music making. Foremost among the many solos performed were those for oboe in the introduction, the slow movement (especially the trill), and the third movement peasant dance, all glowingly played by Bo Newsome. Bassoons, led by Christopher Ulffers, played a vital role throughout. The horns and trumpets came into their own in the finale but had played with great subtlety throughout.

The Piano Concerto No. 12 in A, K.414, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-91) was composed in the autumn of 1782 and was the first of a set of three keyboard concertos the composer performed at his Lenten concerts in 1783. Despite its modest themes and scoring it stands out among Mozart’s early works. The heart of the work is the slow movement which quotes a theme from the overture to La Calamita de Cuori by Johann Christian Bach, who had been such a mentor to Mozart when he was in London. The “English Bach” had died January 1, 1782 and this poignant movement can be regarded as a tribute. Mozart’s scores give no cover for any instrumental flaws. Muti led his superb musicians in a remarkably pellucid performance with all the virtues already mentioned above. The viola section was delightful in its give-and-take with the violins in the opening allegro. The horns were superb in the slow movement.

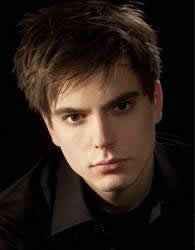

Local Hope Valley native son, Andrew Tyson, has already racked up an impressive resume for a twenty-three year old! Most recently, he won Second Prize at the Kosciuszko Foundation Chopin Piano Competition in Poland. We were impressed when he accompanied Nicholas Kitchen in a November 2010 recital. Beauty of tone, wide color and dynamic palette, and crystal-clear articulation were evident throughout his resplendent performance of the keyboard part of K. 414. His delivery of the cadenzas was exemplary.

The orchestra delivered a fine, warmly played performance of the Intermezzo from Pietro Mascagni’s opera Cavalleria Rusticana led by guest conductor Helen Johnson whose winning bid at a COT Benefit earned her the spot.

The orchestra’s continued service to LIVING composers was amply displayed in the concluding work, Symphony No. 3 (Feb. 1950, rev. summer 1950) by Robert Ward (1917). A recording of this work is still in print on the Albany label. Ward studied at the Eastman School of Music where Howard Hanson was one of his mentors. Studies continued at the Juilliard School of Music where Aaron Copland became a mentor. In addition to his role as a composer, Ward was Executive Vice-President of Galaxy Music Corporation and Managing Editor of High Gate Press in New York for a decade. He was the Chancellor of the North Carolina School of the Arts from 1967-75. After five further years on the faculty, he became a visiting professor at Duke University in 1978 and remained as Mary Duke Biddle Professor of Music from 1979-87. He remains an active as a composer and as a champion of the Arts in our region.

Unfortunately the COT program contained no notes about any of the music played, and talk about new ventures limited Muti’s usual informal introductions to pieces. Ward’s Third Symphony is covered in depth in an article in American Music, Vol. 13, Autumn, 1995, J. Daniel Huband “Robert Ward’s Instrumental Music,” pp.333-356. The slow introduction contains a twelve-tone solo line for oboe and this atonal melody is juxtaposed with diatonic passages to create what Huband calls “a fascinating sonata structure.” Huband calls the second movement, “Arioso,” “perhaps one of the most expressive (con amore) movements penned by an American composer.” A piano is used within the orchestra to deliver a “blues-influenced solo” within a “homophonic texture.” Ward has never been ashamed of being a Romantic and he has always felt “romanticism” has always been present in composition since the Age of Bach. Certainly audiences have voted with their bucks and feet and have vindicated composers such as Ward, Barber, and Menotti, who have held true to themselves against sterile academic fads.

Ward’s tone row frightened no one and his Third Symphony was well received by the audience who warmly appreciated the orchestra’s skillful and enthusiastic performance. Spiky chords opened the piece followed by Newsome’s precise playing of the oboe solo. Passages were taken up in turn by bassoons, and clarinets. The allegro section was full of both dynamic and tempo contrasts. Ward provides plenty of opportunities for every section, including players doing “double duty” such as clarinets and bass-clarinet, oboe and French horn. Kent Lyman played the fine “bluesy” piano part superbly. Since a trumpet was used, Muti was using the revised version which also includes interesting divided string writing. I found the scoring for cellos and violas especially enjoyable. COT ought to commit a recording of this to disc, perhaps coupled with Ward’s Triple Concerto.