Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Lynn Nottage focuses her works around the lives and struggles of black women around the world, a rare and necessary undertaking for the global theatre community. Her play Ruined, derived from true accounts from Congolese women victimized by the war that threatened to destroy their country, has won at least ten awards since its debut in 2008, including the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. Ruined focuses on the lives of four women drawn together in a brothel, which proves their only source of protection during the civil war.

Morag Charlton, set designer for this Burning Coal Theatre Company production, offered possibly one of the most beautiful sets to fill their space in some time. Her stunning portraits of the four African women that bore witness to the story crowned the rugged bar and war-torn Congo with a beauty reflected by the women in the story. Lighting Designer Matthew Adelson enhanced Charlton’s set with detailed specials, warm colors, and often bold punctuations, setting the stage for the intricate story to be told in Ruined.

Mama Nadi (Rozlyn Sorrell), the hardened no-nonsense owner and operator of the bar, offers the only cold beer and female company for soldiers for miles around. Patrons must check their bullets at the bar upon entering and girls are selected to sing, dance, and sleep with any man with ready money, regardless of the side he fights for. With these rules, Mama Nadi is determined to keep military strife out of her bar and her business alive.

The stories of the three women employed by Mama Nadi, Josephine (Sherida McMullan), Sophie (Reanna Roane), and Salima (Madelynn Poulson), introduce unique strength and heartbreak to their universal truth; a brothel where they sell their bodies to warmongers and their blind followers is the safer alternative to the sexual violence these women faced in their home villages. While the playwright speaks little of Josephine’s history except that she was the abducted and abused daughter of a chief, McMullan presented a woman of spiteful strength and almost desperate hopefulness. She seems to evolve as Mama Nadi’s second-in-command, and so abandons most convictions for the sake of the business transaction. She speaks repeatedly of one lover, Mr. Harari (John Allore), a foreign businessman whom she broadly pronounces will take her away one day to the city. Her lack of devotion to him suggests even she holds no faith in her singular hope of escaping her reality.

Likewise, Sophie holds fast to one dream, albeit different from Josephine’s. Sophie, who suffered permanent physical damage from being raped with a bayonet is unsuitable for sex and so considered “ruined.” Well-educated and gifted with a talent for music, Sophie may dream of escaping to the city to live independently, but instead hides away money for an operation to repair the damage to her body. Roanne’s quiet and somber performance painted a textured picture of Sophie: lovely and cunning, but rarely happy.

Salima does not speak of any ray of hope for her future. She refuses her husband when he comes to bring her home, she speaks often of her lost baby, and hers is the only past that the playwright relates in detail and entirety. Her story justifies her absence of hope and precedents the gradual decay of her will to survive. The brave young Ms. Poulson reflects the essence of Nottage’s text in this grisly recount of Salima’s suffering. The content is difficult and so removed from the troubles of a first-world country, many will simply turn away. Nottage and, in this monologue, Poulson have crafted their delivery in such a way that people must hear and see what these women have suffered with open eyes.

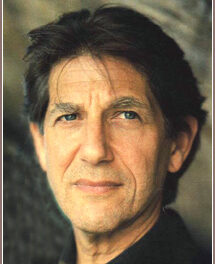

In this production, the pursuit of survival takes precedent over the immediate relationships onstage, making it difficult to know where to focus. Byron Jennings is compassionate and determined as Christian in his affections for Mama Nadi. Sorrell embodies Mama Nadi’s take-it-or-leave-it honesty as she resists Christian and attempts to care for the women in her care. However, the potential for an evolving love between Christian and Mama Nadi and for maternal affection between Mama Nadi and the women is sacrificed by each character’s struggle to survive. Without a central relationship to follow, audiences who are waiting to find out whom to care about may not get an answer. The story of the women victimized by a war they have no stake in is the crux of the play. Audiences should listen to Mama Nadi and Josephine in their acceptance and dogged willfulness to survive and Salima and Sophie who still cope with open wounds inflicted by civil war.

In the current political climate, where legislators light fires under the latest hot topic in a squabble for power, Burning Coal faces us with Ruined. The reality of such violence challenges audiences with a heavy dose of perspective and the focus on African women offers a diversity not often seen in the theaters of Raleigh, North Carolina. It is an important story that Burning Coal acknowledges must be told; audiences must acknowledge it is worth being heard.

Ruined continues through April 28. For more information on this production, please view the sidebar.