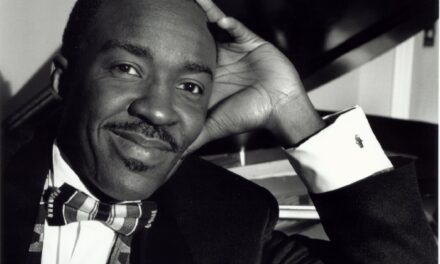

The Asheville Symphony Orchestra performed its second Masterwork Concert in Thomas Wolfe Auditorium sponsored by the Asheville Symphony Guild. Symphony Guild members and a few of their scholarship recipients were on hand to collect donations at intermission for the Guild’s outreach program to schools. Entitled “The Great American Symphony,” the program featured Aaron Copland’s iconic Symphony No. 3 and, in a tribute to Leonard Bernstein’s 90th birthday, the Overture to Candide. Rounding out the musical offerings was Mozart’s Concerto No. 23 in A, K. 488 with soloist Michael Boriskin. André Raphel Smith, currently in his sixth season as Music Director of the Wheeling Symphony Orchestra, was guest conductor.

Bernstein’s Overture to Candide (1956) is a work of lyrical theater based on Voltaire’s cautionary tale. By turns boisterous, lyrical, and rhythmically driving, it has enjoyed an abundant life as a concert overture independent of the stage work. Packed with themes from the show, it’s a bit like listening to a 5-minute Hamlet, as so much is concentrated within its pages. The orchestra was on its toes — nimble, responsive, and secure. Unfortunately, the energy generated by the music was dissipated during the 10 minutes it took to rearrange the stage afterward for the Mozart. In fact, the audience was asked not to wander away, but to stand, stretch, and visit with friends, an intermission before the intermission.

Mozart’s Concerto No. 23 was a personal favorite of the composer, who highly valued its deep and expressive qualities. The piece was completed in 1786 in the midst of Mozart’s busiest years as a soloist in Vienna and was possibly first performed during a series of Lenten concerts held during March of that year. Often cited for its lyricism, the work still has its share of fireworks, especially in the third movement Rondo, as if to remind the audience that, yes, this is a concerto. Soloist Michael Boriskin has performed with many orchestras, among them the Munich and Polish National Radio Orchestra, San Francisco, Utah, and Seattle Symphonies. He also plays copious amounts of chamber music and is currently Artistic and Executive Director of Copland House, a center for American music and a performance venue in the composer’s former home. I could not escape the impression that Boriskin was extremely nervous throughout this performance, constantly shifting about on the bench, playing even small and quiet phrases with huge gestures, and surprisingly, following a score laid flat on the music rack. This raised a whole new set of challenges, as he flipped pages through some of the most difficult passagework, and frequently touched the score, as if for reassurance. His playing seemed overly muted, as though he never found his “soloist’s” voice, and while sufficiently adroit, suffered in some key exchanges from a flatness of dynamic levels and inflections.

The cornerstone of the evening’s program was Copland’s Symphony No. 3, scored for a full complement of strings, winds and brass and including a massive battery of percussion instruments — timpani, bass drum, tam-tam, cymbals, xylophone, glockenspiel, tenor drum, woodblock, snare drum, triangle, slapstick, ratchet, anvil, claves, tubular bells — plus two harps, celesta, and piano. The symphony, commissioned by the Koussevitsky Foundation, was completed in 1946 and premiered with Koussevitsky as conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. It is his most ambitious work in the genre. Copland maintained that no folk song or jazz material was consciously put in the work, and that the only intentional borrowing was the use of his own “Fanfare for the Common Man” (1942) “in an extended and reshaped form in the final movement…to give the Third Symphony an affirmative tone. After all, it was a wartime piece — or more accurately, an end-of-war piece — intended to reflect the euphoric spirit of the country at the time.” Though the entire symphony lasts about 40 minutes, the piece seems to fill a larger block of space in time, so enormous and diverse was the musical imagination of its composer.

The symphony’s cyclic elements — themes once introduced that reappear later — bind the four movements into one entity. The first movement’s opening statements, quiet and lyrically expansive, are one of the work’s foundational sonorities. The third theme represents the other, an extroverted theme played by the brass. Throughout the movement there was a union of intention and expressive aim among the players, who were adroitly led by Maestro Smith. The second movement, a scherzo marked Allegro molto, featured some of the work’s trickiest contrapuntal and rhythmic intricacies — off-beat motivic exchanges, counterpoint in stretto, etc. Here, one had the impression that the conductor’s job was like that of a traffic cop overseeing a merry stretch of musical congestion.

Whereas the second movement was all about movement, the third was about soundscape, and here were some of the evening’s most magical moments — ethereal, wispy sounds in the high strings, unusual instrumental combinations, moods which shifted like sand from overtly declamatory to plaintive to hoe-down to march. The fourth movement follows the third without pause, beginning with the famous Fanfare theme played first by the flutes and clarinets, pianissimo, then forte by brass and percussion. Previous themes are recalled and reshaped, spiced here and there by deliciously dissonant chords and a musical plumbing of our collective memory of the piece as a whole. The Asheville Symphony‘s rendition of this monumental work was uplifting and inspiring, a true reaffirmation of the power of music itself.