Hanging on the walls and dangling from the ceiling of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University is a show that may shock you but that you must not overlook if you value your credentials as an art lover. With an imagination that yokes together the most unlikely bits and pieces from the world we think we know, Wangechi Mutu takes off on a “Fantastic Journey,” both hilarious and grim, weird and beautiful, that runs past our assumptions about race, sexuality, desire, colonialism, and our willingness to see others through distorting mental prisms.

Mutu, born in Nairobi, Kenya, currently resides in my hometown (Brooklyn), but her multimedia work is a worldwide phenomenon. “Fantastic Journey,” including over 50 paintings, drawings, videos, early and late, is the first meaningful survey of her career in the U.S. As the show opened, in fact, she was still at work on a large mural that introduces the exhibition.

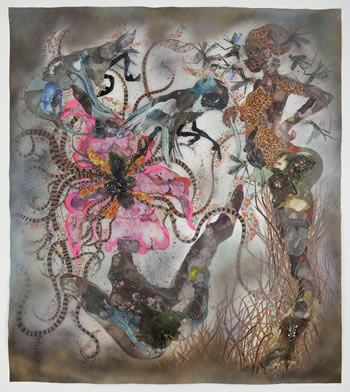

Inside, I found Humming (2010), in mixed media and collage on mylar like most of the wall pieces. In Humming, an exaggeratedly lithe, curvaceous African woman appears on the right, dressed in an animal skin, sporting fake gems on her vaginal area and buttocks, and standing in the high-heeled shoes found on many of Mutu’s figures. She is surrounded by flying insects and faces huge carnivorous blossoms and swirling tendrils from which great winged insects (that the wall note somehow identifies as humming birds) seem to emerge. Below, we see what may be a fallen man. Humming clearly presents the image of the black African lady as both alluring and destructive. But the tentativeness in my description – “seem to,” “may be” – indicates the dualities and spread of possibilities Mutu herself speaks of. After all, though the woman is essentially a comic character, she is beautifully portrayed. And Mutu is quoted as insisting that her work is a journey of self-discovery.

Comic too is the root in The Root of all Eves; a stunted black female holds her legs up to reveal her vagina (Africa, we may remember, is the ancient source of humanity). She is below ground but long strands of hair reach up to entangle the legs of an obviously wayward woman wearing motorcycle goggles. Out of Africa came man and all unredeemable Eves. The entire painting is in deep scarlet and shadow.

But just beyond the doorway I found the far more positive Yo Mama, a strong homage to a strong Kenyan woman described by Mutu as a “visionary and brave fighter.” She is shown here decapitating a huge phallic snake emerging from a swamp into an otherworldly environment where its head is pinned by her heel. And in the large double canvas Shady Promise a woman straddles the upper branches of a thick tree, bending them so that they seem to become roots replanting themselves. The woman is apparently masturbating. Though, of course, she provides no seed, no promise, she does signal her identity as one with the natural realm. At least that’s one reading.

The exhibition permitted Mutu to venture into a new area – that of the animated video. Commissioned by the Nasher, The End of eating Everything slowly, ponderously and imaginatively takes aim at our tendency to eat or consume our world. A shapeless planetoid covered by patches of infection and worms moves against a bleak sky filled with circling birds. At one edge of the land Mutu has placed the feeding head of the black recording artist Santigold; with her mouth wide open she lunges at the birds, consumes and consumes and ultimately explodes. Interestingly, another video employs the hymn “Amazing Grace,” the words created by an English slave trader turned anti-slavery preacher. As we hear the song, translated into an African dialect, a woman in white walks into the sea and, presumably, is washed clean of her sins.

Curated by Trevor Schoonmakber, Nasher curator of contemporary art, the show will eventually travel to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami and Northwestern University’s art museum in Evanston, Illinois. It will remain here through July 21. For details, see the sidebar.